Understand

A general open digital ecosystem model

The growth of digital systems and the adoption of APIs require a new business mindset. We call this ecosystem design thinking. But how do you get started understanding your own open digital ecosystem: whether that be at the industry, subsector, local or organisational level? A general open digital ecosystem model can help you start defining specific stakeholder groups and actors relevant to you.

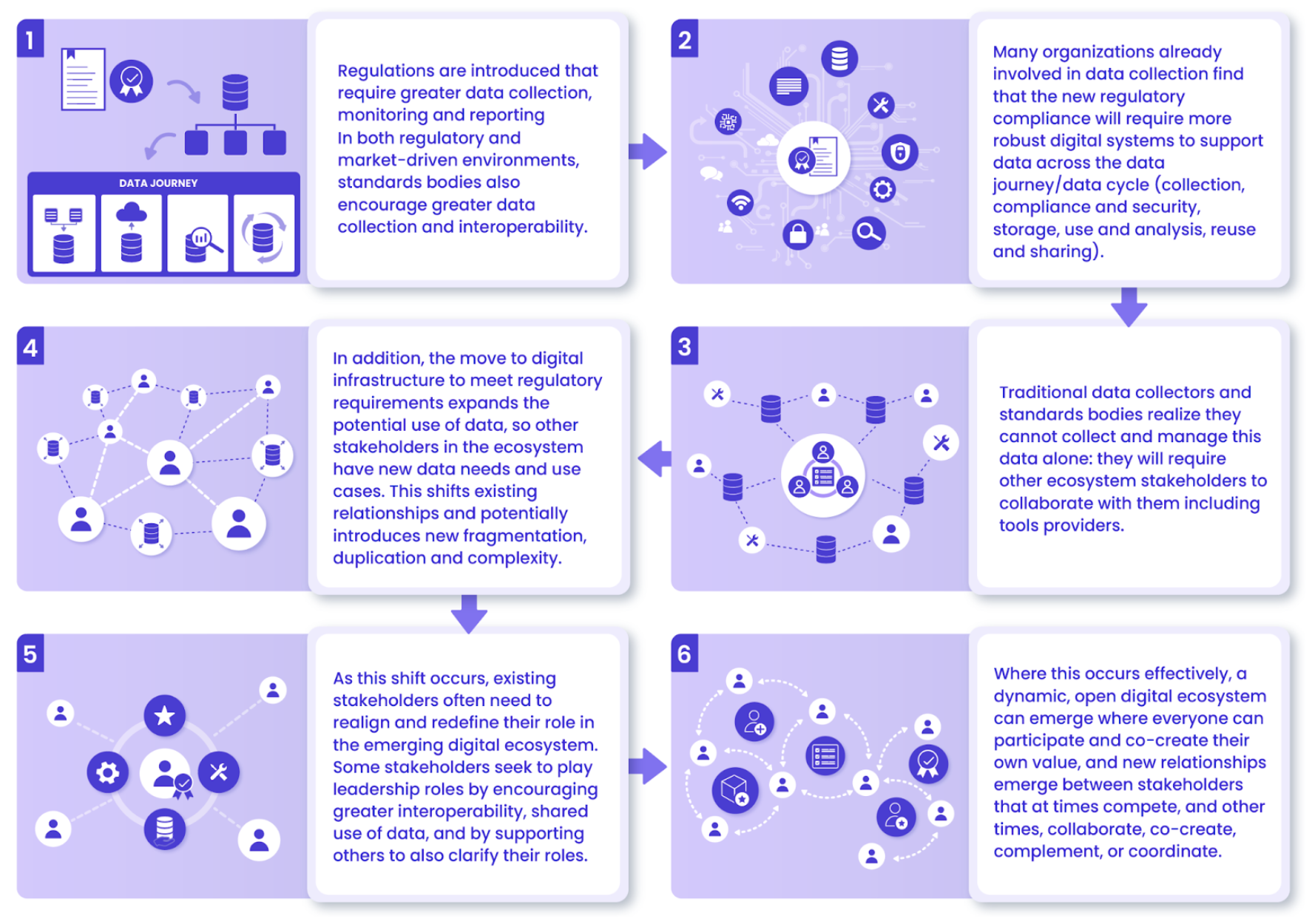

The emergence of open digital ecosystems

In our post on cultivating an ecosystem mindset, we describe how ecosystem thinking is needed arising out of:

- The convergence of digital systems

- The increasing use of data

- The use of regulations as an instrument to force greater data reporting, and

- The maturing of standards (and greater willingness for standards adoption amongst more commercial stakeholders)1.

Ecosystem mindset thinking has become an essential skill for organisations operating in highly regulated industries including open banking/open finance, digital health, agrifood, and the traceability of supply chains.

Over the past five to ten years, and last two years in particular, the adoption of APIs has also grown significantly. Already powering somewhere between 60-80% of all internet traffic, multiple data sources report a surge in API growth2. APIs (application programming interfaces) are digital components that allow systems to connect, for organisations to expose their data and digital services in machine-readable form, and to programmatically define contractual relationships around who can access data and services and under what circumstances. APIs are a core technology that foster digital ecosystem growth.

Ecosystem design thinking

Our overview of an ecosystem design thinking process describes the elements that make up ecosystem design thinking and how it differs from more traditional market research and strategic planning. What is needed to start ecosystem design thinking is a model of how your ecosystem operates. Mapping this ecosystem model involves:

- Understanding the context including the use of standards, market-driven initiatives, and regulatory requirements

- Understanding end user needs including data on how users behave digitally, the level of consumer digital readiness and industry digital velocity

- Listing available APIs and data products, as well as tracking which digital businesses use which APIs (where possible)

- Listing available common components, digital tools, digital public infrastructure, open source tools, and proprietary products and services that enable digital ecosystems to operate

- Linking the impacts of digital product and service provision to goals aligned with sustainable development (that is, measuring the benefits and risks for society, local economies, and the environment).

By collating all of this data, and looking at gaps and opportunities, it is then possible to consider how to enter a digital ecosystem, defining what role and position you want to take, and identifying what levers you can apply to act. (Which may lead you to invest in creating an interoperability toolkit, defining API contracts, focusing on data governance and/or API governance, and so on.)

A general open digital ecosystem model

For any given industry then, an initial step is to map the ecosystem. This can be done at a number of levels:

- At a global level: Useful for sectors where cross-border transactions and global markets are common. Digital solutions need to use standards and common digital tools and infrastructure to prevent barriers to trade, fragmentation, or duplication.

- At a a country or region-wide ecosystem level: Useful when there are specific regulations that are required in a specific geographic region (such as at the country or regional level) that requires additional digital tooling and infrastructure to enable regulatory compliant transactions within a country or region.

- At an organisational level: In this new digital transformation era, organisations act as platforms, not just making end products and services available but also making digital components like datasets and service functionalities (APIs and open source tools) available to others who can build their own solutions. The organisation has greater say over who can participate in their ecosystem and can set their own rules for engagement, but in regulated industry sectors, each of these ecosystems will still have to align and comply with the geographic or global ecosystem context.x

There are other lenses that can also be applied. This can be based on mapping a subset of the ecosystem. For example, in digital health, it would be possible to track an ecosystem based on a burden of disease or even a type of therapeutic intervention (or both!). If you are looking at the diabetes management digital health ecosystem, you might map the ecosystem for diabetes, or even the diabetes digital app management ecosystem.

Mapping the ecosystem

There are a number of methodologies that can be applied. One of the most common is to focus on the mapping all of the stakeholders and their relationships.

We find this can be a challenging way to start for two key reasons:

- Starting with a blank canvas can be a challenge and often leaves out key players. For example, when we have seen this process used in digital health, we have seen data protection bodies left off the stakeholder map, who have a large say in access and use of health data. In sustainable aviation fuel ecosystem models, we saw ecosystem mapping leave off regulators, brokers and marketplaces, auditors, and standards bodies.

- Starting with a blank canvas can be daunting and slows down the process, especially when participants have limited time to work together in a workshop setting to map stakeholders.

Ecosystem models that focus only on stakeholders and relationships miss much of the context, especially around digital public infrastructure components (which in turn gives insight into other stakeholders that were perhaps invisibilised as they provide the underlying infrastructure).

We have developed ecosystem models for the industry sectors we work in: banking/finance, health, intellectual property, and traceability of supply chains. We find that when brainstorming in a workshop setting, we can use these models to quickly start identifying the various players in each stakeholder grouping.

To aid other sectors in ecosystem mapping, we have developed a general ecosystem model that can be adapted for any specific industry sector as needed:

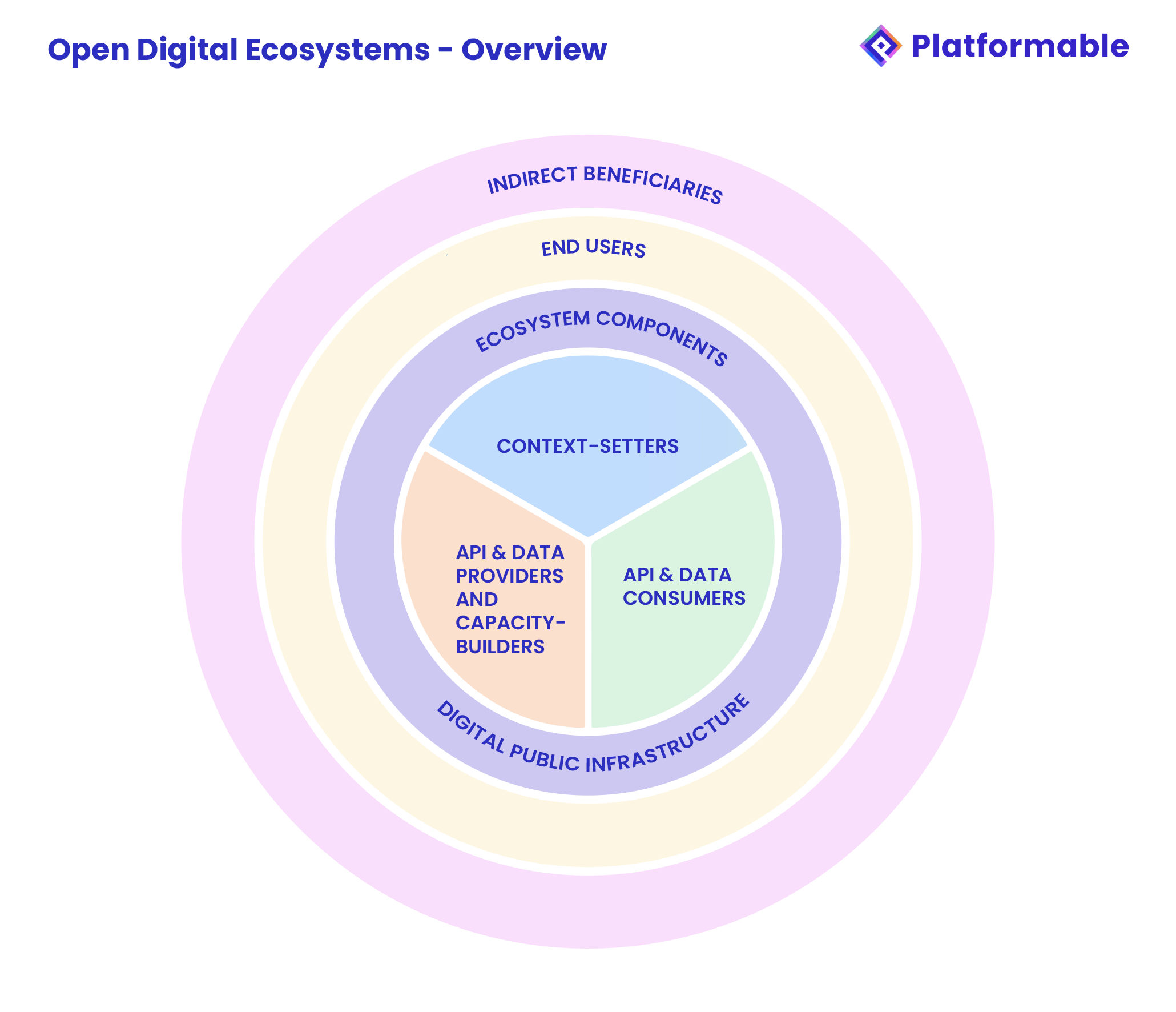

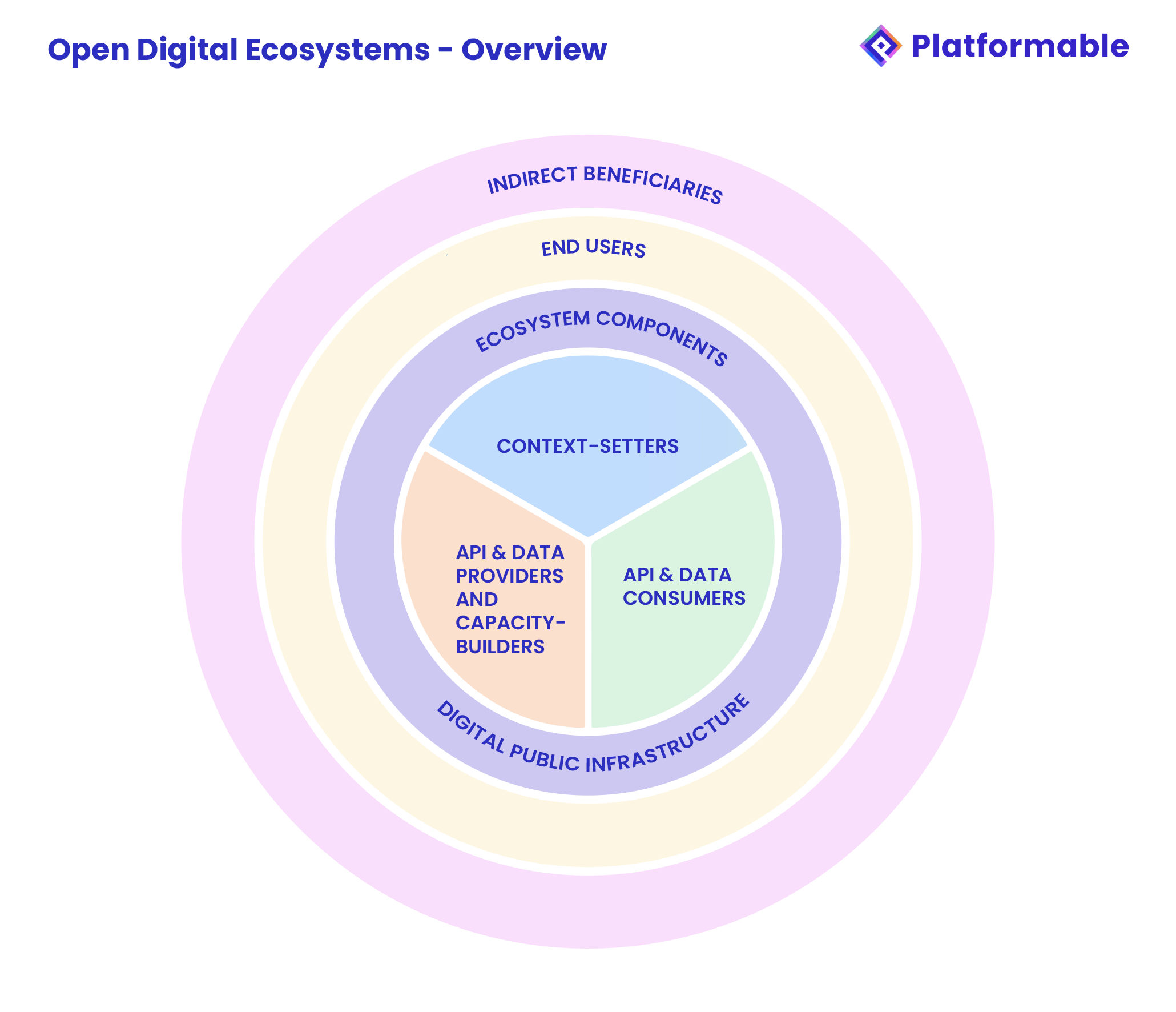

At a high level, an ecosystem is made up of three participants:

- Context-setters

- Data and API providers and

- Data and API consumers.

Stakeholders in any of these three groups can decide to play a leadership or participatory role in a digital ecosystem. For example, regardless of where an organisation is situated in these three groupings, they can be an orchestrator (encouraging ecosystem maturity for all stakeholders), a facilitator (working with their own members and partners to encourage full participation in an ecosystem), or a participant (focusing on one's own organisational role in actively participating in an existing or emerging open digital ecosystem).

Context-setters, Data/API providers and data/API consumers draw on a range of artefacts like policies, regulations, standards, APIs, data models, user agents, and digital tools to facilitate activities within the ecosystem. These ecosystem components may be proprietary or public digital infrastructure.

Stakeholders then create digital products, services, workflows, and other solutions aimed at supporting some type of end user. End users could include individuals and households, other businesses and enterprises, other types of organisations, researchers, media, and so on.

The ultimate goal then of the ecosystem is to provide services and value to end users as well as value back to the providers or consumers who create the services/products, but also to support wider, indirect beneficiaries. For example, digital products and services may reduce the need for community members to attend a physical office or wait in line to book an appointment. At a societal level, this could increase access to services, reduce waiting times, and enable greater choice. At an economic level, it allows those waiting for services to continue in their employment rather than take time out to attend services or make purchases, it might stimulate new demand which drives new employment, and ideally, it means digital businesses are created that also hire people and pay taxes to support local economies. From an environmental point of view, resources can be used more efficiently, reduce the need for transport or fuel consumption, and if IT systems are built well, they can be optimised to reduce waste and be more energy efficient.

Getting started

Using this above model may be enough to start listing all of the stakeholders and components in an ecosystem.

Personally, I prefer a map with a little more description that breaks down elements into smaller groupings that perhaps also show the process or flow of how value is generated and distributed in an ecosystem.

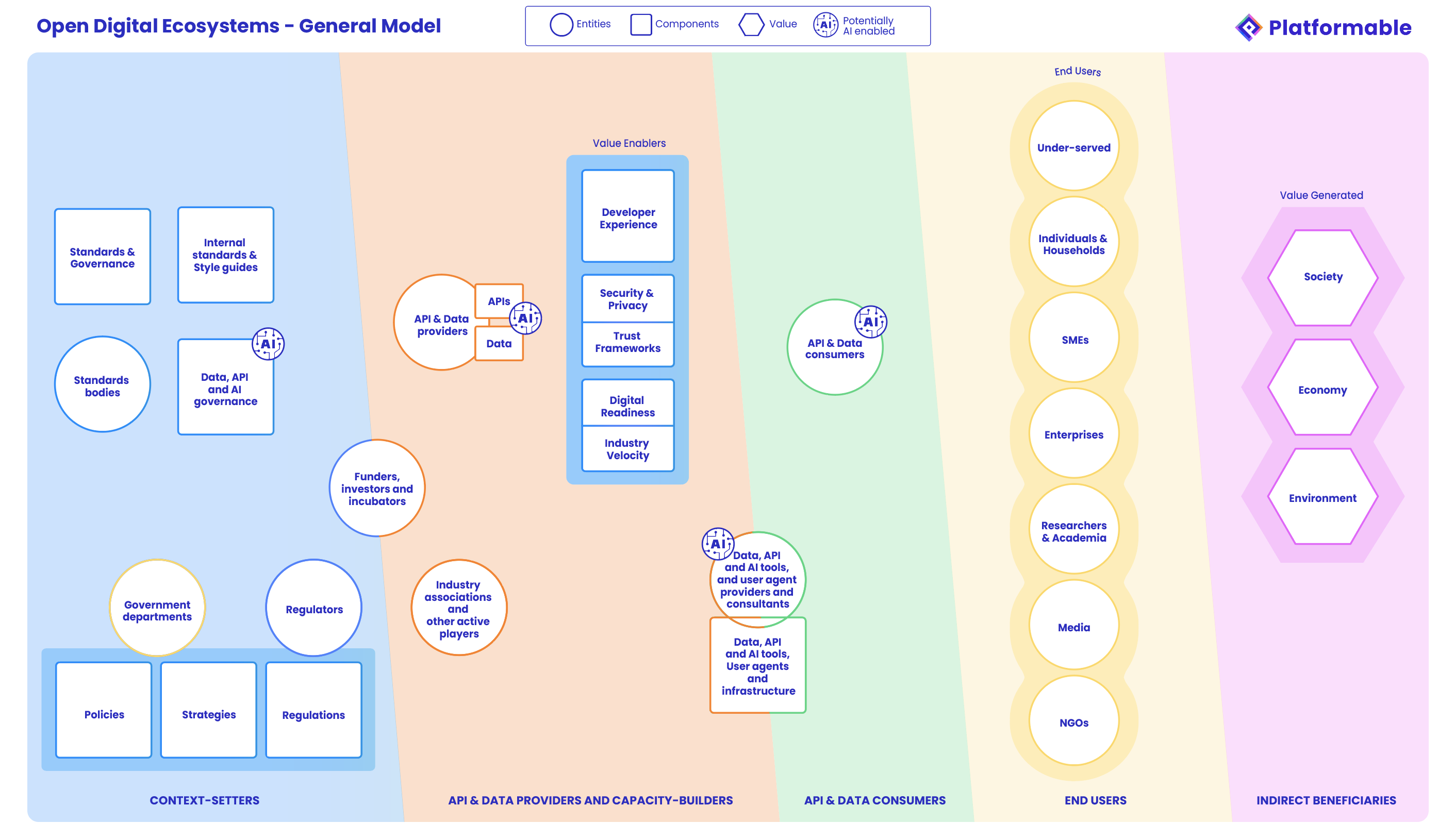

For this we have mapped the general ecosystem model in more detail:

This diagram describes the following stakeholders:

Stakeholder | Type | Description |

Standards bodies | Context-setters | Broad standards organisations (and market-driven initiatives) that define specific data standards and data models used across industry or seek to establish norms for industry interoperability and data sharing |

Regulators | Context-setters | Defined bodies responsible for establishing regulatory compliance processes and for using and assessing data |

Government departments | Context-setters | Policy making government bodies that draft and implement legislation, policies,, guidelines and strategies that set the ecosystem context |

Funders, investors and incubators | Context-setters Capacity-builders | Bodies that provide funding and investment can be both capacity builders and context-setters. As context-setters they are stimulating market entry and also setting what priorities should be focused on by ecosystem actors. As capacity builders they are providing financial resources to enable ecosystem growth. |

API & Data providers | API & Data providers | Stakeholders that make data and services available digitally and in machine-readable formats to others to use as materials to build with are API and Data Providers. |

Industry associations and other active players | Capacity builders | Capacity-building organisations (including multilateral organisations) create tools and resources to support ecosystem activities. Industry associations, consumer representative organisations, traders associations and other bodies also participate in shaping the ecosystem and supporting their members and constituents to build capacity and to be able to participate actively. |

Data, API and AI tools, user agent and infrastructure providers and consultants | Capacity builders API& Data consumers | Stakeholders assisting other actors to participate in open digital ecosystems by providing datasets and/or digital tools to meet regulatory requirements, by providing underlying infrastructure to enable product development and ecosystem participation. These tools providers may also consume data and APIs in order to provide features in their own products and services as well. Includes open source projects and tooling, and digital public infrastructure. |

API & Data consumers | API& Data consumers | Stakeholders that integrate data and APIs into their products and services. These can include B2B tools providers servicing a particular sector, or some end user stakeholders who also consume data and APIs directly. |

End users | End users | Stakeholders that make use of digital products and services directly or indirectly that have been provided through an open digital ecosystem. Typically includes: under-served/marginalised populations, individuals/households, sole traders, micro-businesses, SMEs, enterprises, media, academia and research institutions, and non-profit organisations. Some of these end users may also be directly consuming the data and APIs for their own use as well as those end users making use of products and services that have consumed the data and APIs. |

Society | Indirect beneficiaries | Societal benefits from open digital ecosystems such as broader consumer choice, more equitable participatory opportunities, less friction in service and product access, and so on. |

Economy | Indirect beneficiaries | Local economic development benefits from open digital ecosystems including business diversity and strength, employment growth, and increased tax revenues collected. |

Environment | Indirect beneficiaries | Environmental benefits from the better management of resources by using data and digital systems to optimise use of resources and create efficiencies. |

Components tend to include:

- The regulations and standards themselves and any government policies and strategies that define how the industry sector must operate.

- Standards and data governance, including internal standards and style guides and best practices and tools, including in data, AI and API governance frameworks such as consent processes that ensure that data subjects maintain control over how their data is used throughout the ecosystem, and trust frameworks that can include tooling to enable responsible data sharing at scale.

- Developer Experience refers to the resources made available to API and data consumers to assist them to onboard and build successfully with data or APIs.

- Security and Privacy refers to the level of security and privacy robustness of data and APIs, and ease in enabling data protection regulatory compliance and use of security best practices. These impact on the overall trustworthiness of an open digital ecosystem.

- Digital readiness refers to the level of skills and expertise amongst potential API and data consumers, and the digital readiness of end consumers to make use of digital products.

- Industry Velocity refers to the overall subsector or industry's willingness and capabilities to move to data- and API-enabled digital approaches.

- The data, AI, API, and digital tools including user agents and infrastructure that support open digital ecosystem growth. This can include open source tooling and other digital public goods that are shared or can be used by any ecosystem stakeholder, as well as proprietary offerings that must be purchased or are only available to specific actors. This can also include the hardware level and the cloud infrastructure that digital is built on.

Proprietary tooling vs digital public infrastructure

Our ecosystem model includes components that can be considered digital public infrastructure and proprietary elements. Defining digital public infrastructure can be a challenge4. The UN describes digital public infrastructure as "a set of foundational digital systems that forms the backbone of modern societies. DPI enables secure and seamless interactions between people, businesses and governments"3.

But this still presents some challenges. Some open source and proprietary software and tooling is provided free of charge and is available to everyone to use.

Are all free tools digital public infrastructure? I would not necessarily include freemium Software-as-a-Service as digital public infrastructure. But tooling that monetises in other ways I would class as DPI. Search engines, browser software and social media platforms are examples here. DuckDuckGo, Vivaldi, and Bluesky could be considered digital public infrastructure (ok, we can also say Google, Chrome, and Twitter here). These types of DPI are widely used and are often the conduit to access digital services. They require a particular type of oversight to ensure that they are not extractive or manipulative.

I would also class some APIs as digital public infrastructure: government APIs are an easy one to classify as DPI, but I would also include bank APIs, at least the payments and bank account information APIs. These are predominantly required under regulation to be made available for free.

Alongside these DPI components are proprietary tooling and infrastructure that also enable ecosystem activities. The most obvious example here are cloud providers. Cloud services are essential to enabling digital ecosystem capabilities, but they are proprietary. Open source cloud infrastructure might be public digital infrastructure, but this is often tightly coupled with cloud services provision: the memory allocation that enables data to be stored and computed in the cloud. There are good arguments to ensure that there is a plurality of cloud service providers to prevent brittle digital ecosystems that have single points of failure. Plurality of services is also important for load balancing and content distribution networks as well, which have been responsible for many of the global outages due to over-consolidation in this part of the market.

Using the ecosystem model

Adapt the general ecosystem model to the level of analysis you want to make

This could be:

- Global

- Country-level

- Industry-specific

- Sub-sector specific

- Geographic and industry- or subsector-specific

- Granular

- Organisational level ecosytem.

Adapt the ecosystem model to re-align categories, as needed

Sometimes there is the need to add new stakeholder groupings, or ensure certain bodies are represented. For example, in our banking/finance model, we added financial inclusion advocates as a specific category grouped with consumer and industry associations. We also identified distribution channels (like app stores) that help make fintech apps available to end users. For health, we added health data access bodies, a relatively new type of organisation being introduced in Europe and globally to oversee whether personal health data can be accessed and used between data and API providers and data and API consumers.

Separate categories into sub-categories

These steps include:

- Classify API and data providers into sub-categories. For example, in our health model we break this down into government, healthtech and health providers.

- Classify data and API consumers into sub-categories. For example, in banking/finance we break this down into banks, fintech, aggregators, marketplaces, and so on.

- Classify end users into sub-categories. For example, we tend to use under-served communities, individuals/households, sole traders, SMEs, enterprises, media, research, and government as typical types of end users.

- You may wish to further classify indirect beneficiaries into sub-categories. For example, following work we did with the WHO, we identified 6 key values/benefits that stem from greater use of health data, so we use those categories in our ecosystem model.

- You may also wish to classify API, data and AI tooling providers into sub-categories. For example, for our traceability ecosystem model, we look at consultants, due diligence software vendors, satellite and mapping software vendors, and so on.

Start listing all known stakeholders in each category

Now comes the real work of the ecosystem modeling. Start to brainstorm all of the individual stakeholders and components that you are aware of for the given level of granularity you have decided on.

Add data about end user needs and indirect beneficiary impacts

Some of the components lend themselves to benchmark data or the collection of industry user insights. For example, when we look at digital readiness in the banking/finance sector we look at number of people who checked their bank balance or made an online payment in the past 12 months. For end users, we tend to create folders where we can store industry research and data as we gather it. For example, for health, there is regularly reported data on burdens of disease by age, gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation and so on. You can also add your own data on your user needs to this collection.

What next?

This is should now be treated as a live resource for your organisation. You will want to keep adding to this as you go, identifying more stakeholders and components.

We use a database to keep all of this data organised, but we started with spreadsheets. We are now building visualisation tools for some of this: we will be releasing our early prototypes for banking/finance, health, and traceability in the coming weeks.

Map strength of relationships and influence

You may want to review where you have strong relationships with other stakeholders, and identify where you will need to build relationships. Maybe you have identified key influential organisations that you need to participate in (such as industry associations or standards bodies).

Look for gaps and opportunities

Are there areas where there is limited tooling or a low number of relationships, but high end user needs? Using regulations to forecast future needs, are you partnering with stakeholders who can support you to meet new regulatory requirements?

Review our ecosystem design thinking post to see more ideas on how to use your ecosystem modeling to make strategic decisions.

We will continue to share resources on ecosystem design thinking, and will be working in the open to share our progress when we commence this work in a new industry sector. If you are interested in learning more about this approach and how it has supported various businesses and organisations, please get in touch or book a meeting on our calendly.

Article references

The influence of regulations and standards on ecosystems might wax and wane slightly: some might argue, for example, that the rapid deregulation in the United States and in the Competitiveness Compass omnibus package aimed at 'simplification' of European regulations point to a weakening influence of regulations. But in many ways, tariffs are a form of regulations — imposing rules on how supply chains can be managed — which reasserts the need for digital and data-enabled systems that allow market analysis and decisive action. We also expect to see a return to some market-driven approaches that set industry norms. Standards also appear to be insufficient in themselves in driving ecosystem-based approaches, giving rise to the need for "post-voluntary standards".

See the API State of the Economy Report 2024, published by apidays, and available for download.

Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) is a set of foundational digital systems that forms the backbone of modern societies. DPI enables secure and seamless interactions between people, businesses and governments.

See https://euro-stack.eu/digital-commons-and-the-european-dpi-agenda/ for a discussion.

Mark Boyd

DIRECTORmark@platformable.com