Understand

Analysing open ecosystems: the new skill needed for 2024

The adoption of digital infrastructure, greater use of data, and building of APIs to enable composable product development in key industry sectors has encouraged many organisations to move towards a platform-and-ecosystem approach in one of three ways:

- By becoming a platform, where as an organisation, you have repackaged some of your digital services, APIs and data as products that can be used by others to create new value chains

- By becoming an ecosystem partner, in which as an organisation, you now make use of data and services provided by others. This is often done by integrating their APIs or data into your products and services to provide functionalities that you don't want to build yourself (like using a payments API) or to extend the feature-set of your products (for example, by buying and integrating external datasets) or to enable automated workflows for some of your processes (for example, by using email APIs, or to enable observability of your own infrastructure), or

- By becoming both a platform yourself and an ecosystem partner in an open ecosystem or in some other organisation's ecosystem.

Open banking/open finance and open health are two areas where this is most prevalent, but other industries are maturing as well: logistics, airline industry, travel, automotive and transport, sustainability, energy, trade, manufacturing, intellectual property, and agriculture, for example, all have emerging open ecosystems at local, national, regional and/or global levels (to varying degrees of maturity).

Analysing an open ecosystem for product market research and general participation

In a similar way to market research and business analysis (what we often call business intelligence), if we had better approaches to mapping and measuring open ecosystems, you could get better answers about who to partner with, what products to build, how to build those products and so on (ecosystem intelligence).

For example:

- What are the most unmet end user/population needs?

- What data and APIs are available and who are the data providers and API providers?

- What regulations are required in each country for operating in this ecosystem?

- What businesses and organisations are available to partner on solutions?

- What standards and data models are most commonly used in the ecosystem and what standards bodies could I be part of?

- What marketplaces, industry associations and API tools are most relied on in the ecosystem?

- What business models and pricing strategies are being used by others in the ecosystem?

If we look just at the open banking/open finance sector, various actors could ask:

Sub-sector of ecosystem stakeholders | Icon | Key questions these stakeholders could ask when analysing open ecosystems |

|---|---|---|

| Financial inclusion advocates |  |

|

| Fintech associations |  |

|

| Fintech |  |

|

And if we look at open health, actors could ask:

Sub-sector of ecosystem stakeholders | Icon | Key questions these stakeholders could ask when analysing open ecosystems |

|---|---|---|

| Health Equity Lead |  |

|

| Incubators and Challenge Creators |  |

|

| Data Governance Lead |  |

|

Analysing an organisation's ecosystem to determine potential involvement

Ecosystem modelling and analysis also helps you determine whether an organisation's own ecosystem is something you would like to enter. When analysing an organisation's platform approach before you decide to build in their ecosystem, you would review data on:

- API availability (and the developer experience score)

- API Terms of Service

- Mandatory regulations

- Use of standards and data models

- Other ecosystem stakeholders and their offerings and potential for partnership opportunities, and

- Any industry association-type gatherings within the ecosystem.

Analysing an open ecosystem to determine whether to become a platform

If you are thinking of moving to a platform-business model, you might want to look at your industry's open ecosystem to determine how much work would be involved in building out your ecosystem, and where to start. To decide what to build, how to price your APIs and who would be most ready to start using your APIs when you have them available, you would review data on:

- Regulations

- Existing use of standards

- Quality of currently available APIs (and how they differ from your)

- API business models and pricing strategies

- Availability of API consumers to build their products using your APIs Most popular API tools used in your industry

- Level of digital readiness and security perceptions, and

- Availability of distribution channels.

The challenge of current approaches to analysing ecosystems

The Gartner Hype Cycle is a recognised and well-respected approach to assessing the maturity of new technological approaches. It shows technology goes through an initial spike of interest and excitement (the innovation trigger) until it reaches a point of peaked expectations. As users adopt the technology or technological approach, it is discovered to not meet each individual user's needs, and plummets into a trough of disillusionment as users struggle to adapt the technology/approach to their use case and existing systems while providers adjust their product-market fit and featureset to address these concerns, until (hopefully) the technology climbs a slope of enlightenment and plateaus as productivity is harnessed (and new technologies and approaches are needed to innovate further, leading back to another innovation trigger).

At a conference on APIs hosted in June by the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO), VP Analyst and Chief of Research, Software Engineering, Mark O'Neill, shared Gartner’s 2023 Hype Cycle for APIs which showed that while business ecosystems themselves have reached peak expectations and will now crash into the trough of disillusionment as organisations seek real value and reach productivity (a process Gartner forecasts will take 2-5 years), business ecosystem modelling is only just entering the API Hype Cycle as an innovation trigger.

Gartner's predictions mirror what we see in our research and industry discussions. At present, other approaches to ecosystem modelling really mean showing who is getting investment in an industry: the work of Crunchbase, CBInsights, Dealroom, and others. But this only shows what investors (a predominantly white and male industry that has historically continued to fund white and male-led businesses) are investing in, rather than what ecosystem stakeholders and end users need. We have seen this ourselves when attending open banking/open finance events. It is not unusual to hear that a fintech startup strategy is to keep tweaking their product until they land a large enterprise customer (that will keep early investors happy) and then they plan to sell to that enterprise customer's competitors as well when they have demonstrated the product-market fit/need.

We also regularly hear about the struggles our clients face. They have challenges understanding the players that are in their ecosystem, who could be approached to join their ecosystem, who are in their competitors' ecosystems, what product ideas could be built, what regulations govern their sector that they need to keep an eye on, what standards they should be adopting, and so on. Our datasets are helping them, but that requires users to have a mental map of how it all fits together so they know what questions to ask of the data to drill down.

While Gartner has business ecosystem modelling at the start of the innovation trigger stage, we think it will catch up with business ecosystems in the trough of disillusionment: the modelling is what will help the business ecosystems themselves rise into the slope of enlightenment.

In health, the work of identifying greatest challenges, or of mapping population health data needs, is often seen as a separate task to ecosystem modelling, and is used more as justification or initial market research for healthtech. Or healthtech startups have emerged because teams have already worked in the health sector and have found a gap or challenge they think they can address through a new solution. Often governments will produce health plans and establish funding pools to address specific needs, but that can also lead to duplication or projects that are built just for the investment funding as a pilot or prototype that have no real business plan or sustainable strategy for management beyond the funding period.

The work of identifying needs, mapping standards and data models, researching available data and APIs, understanding what regulations need to be addressed, and which stakeholders are available for partnership is repeated for each project.

New approaches to understanding and engaging with open ecosystems

At Platformable, we have focused on the 'innovation trigger' of ecosystem modelling for some time. Our approach involves:

- Regular discussions with clients and wider industry stakeholders in the API space and open ecosystem world

- Ongoing desktop research from industry and academics on innovation ecosystems, open ecosystems, digital ecosystems, platform models, and so on

- Creation, testing and validation of value models that map how value is generated and distributed in an open ecosystem (this has also required the creation of multiple taxonomies, including taxonomies to categorise different types of value, different stakeholders in an ecosystem, and different types of relationships in an open digital ecosystem)

- Drawing on our data governance approach, we have used these value models as our program logic flows (or operational frameworks) to identify existing datasets and to design new datasets for creation and collection

- Regular collection and analysis of data using these taxonomies and models.

We are finding that this is a more engaging and successful way to discuss the gaps, challenges, and opportunities available than using the existing approaches that focus more on a list of businesses operating in a sector and what investment they have received. Others agree with us: we have four large globally-focused universities and a global enterprise customer that all work with our open banking ecosystem datasets for example, and our open health ecosystem work was used in pre-reads for a Data Governance Summit by the World Health Organisation, which was referenced in the formation of the Health Data Governance Principles by Transform Health.

While we have specific open ecosystem value models for open banking/open finance and open health, we have also created a more general open ecosystem value model that we have successfully used in other industry sectors. While tracking how value flows, it also describes all of the stakeholders and key components in an open ecosystem and can be used as a high level open ecosystem model.

Open ecosystem components

Icon | Stakeholder/ component | Definition | Example of metrics that could be collected for analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Governments | Governments help facilitate open ecosystems. They initiate regulations to govern open ecosystems, invest in open ecosystem components and fund and encourage participation of stakeholders, monitor the impacts of open ecosystems, and so on. Number of governments with regulations governing open ecosystems. | Number of governments developing regulations or processes to guide open ecosystem development. |

| Regulators | As either government departments or regulatory authorities established as independent organisations separate to government, regulators oversee and monitor the implementation of regulations that often define the rules of engagement and operations within an open ecosystem. |

|

| API & Data Providers | Organisations that release APIs and datasets for others to use as building blocks are providers in an open ecosystem. | Number of industry-specific API providers in the open ecosystem. |

| Standards and Protocols | Standards and protocols are agreed (or encouraged) interoperability approaches used within an open ecosystem to define APIs and datasets. Sometimes, these are mandated by regulations, sometimes they are adopted by industry, and at other times they emerge in a bottom-up manner where sufficient levels of stakeholders have adopted them that they become a common standard used by various ecosystem stakeholders. | Number of relevant standards and protocols used by stakeholders within the open ecosystem. |

| Standards bodies | These industry associations and international organisations and bodies may have governance and oversight of particular industry standards or open data models that are used by ecosystem stakeholders within an open ecosystem. | Number of standards bodies overseeing standards that are used in the open ecosystem. |

| API & Data Governance | While some ecosystem maps might solely focus on the stakeholders, Platformable’s model also includes core concepts and approaches that act to mediate the value that flows in an open ecosystem. API & Data Governance is recognised as an independent process/approach, akin to a stakeholder as it is often implemented by a team or leader within an organisation, that helps determine the quality of the APIs and datasets provided by providers by clarifying how APIs and datasets are defined and oversees their use and sharing which, like with standards and protocols, may at times be regulated or otherwise voluntarily implemented. API governance refers to the policies and processes that make it easier for API providers to introduce standards and consistent design practices. Data governance refers to the policies and processes that ensure that data is managed ethically, responsibly, equitably, and securely within an organisation and with partners and other external users at all stages of the data journey. |

|

| APIs | Application programming interfaces (APIs) are connectors provided by API providers that link systems, services and/or datasets together using a clear contract that describes what can be shared between systems and how access should be managed. | Number of APIs (categorised by functionality) available to the ecosystem. |

| Developer experience (DX) | In an open ecosystem, developer experience refers to the ease of understanding, user-friendliness, and range of capabilities of APIs, datasets, and associated tooling available to support the building of solutions, and consumption and management of APIs. A high developer experience allows developers to avoid regularly interrupting their workflows to solve challenges in order to better make use of the APIs. |

|

| Security and privacy | The level of security and privacy of available APIs and datasets influences the level of value that can flow in an open ecosystem in two significant ways: (i) if APIs and datasets are insecure or make use of sensitive data inappropriately, it breaks the trust of end users who are then hesitant to use digital products and services built with these APIs or datasets and (ii) insecure APis and those that make use of sensitive and personal data without appropriate guardrails create a business risk for both the providers and API consumers which can limit the interest in building products and services in an open ecosystem. | Number of data or security breaches in the ecosystem in the past quarter. |

| Digital readiness | To foster an open ecosystem requires that API providers, consumers and end users all have a sufficient degree of digital readiness: API providers must provide stable and sustainable APIs and datasets that are well designed and take a product management approach, API consumers must have sufficient digital skills and technical capabilities to build with APIs, and end users must be willing and have sufficient internet access to make use of digital services on a regular basis. |

|

| API tools providers, technology providers and consultants | Supporting API providers and consumers to define their platform and ecosystem play, build, manage and consume high quality APIs, ensure security, enable developer experience, track value generation, and monetize business models amongst other tasks are often performed by API industry-specific and wider technology providers and consultants. A wide range of open source tooling (supported by varying degrees of active communities) are also available. |

|

| Industry associations | Professional associations representing industry members often support API providers and/or API consumers and help track ecosystem stakeholders at a geographic level. They may advocate for greater participation in policy decisions on behalf of their members, help explain key regulations to their members, encourage new product development that address gaps, share understanding of trends, and so on. | Number of industry associations operating in the ecosystem and size of their membership. |

| API Terms of Service | API Terms of Service are the contracts that explain the allowable uses of an API and sometimes the data or services that are transmitted via API. While underutilised as a business or ecosystem tool, API Terms of Service could have a significant impact on an open ecosystem by defining the norms of using data and APIs, and foster clarity and trust amongst stakeholders, as well as give assurances for business model development based on consuming APIs. |

|

| API Consumers | The businesses and organisations building products, services, workflows, and tools that make use of data and APIs available in the ecosystem. Depending on the ecosystem industry sector this can also be broken down into sub-categories of consumers. For example, in our open banking/open finance ecosystem model, we have identified general fintech, aggregators, marketplaces, distribution channels, banks and researchers as potential API consumers. In health we have identified healthtech, pharmaceutical companies, insurance providers, governments, media, researchers, and so on. |

|

| Consumer and community advocacy organisations | Consumer and community advocacy organisations often advocate indirectly around APIs and data, for example, by advocating for greater interoperability between systems and service providers, by advocating for tools to be built to serve under-served populations or to reduce digital inequities, or by advocating for greater data protections. Many of these advocacy efforts, however, directly impact on how APIs should be built and managed. |

|

| End users (for example: Under-served, Individuals and households, SMEs, Enterprises) | Sub-populations (that can be categorised according to the open ecosystem) that use digital products and services that have been built using APIs and datasets. For example, electronic health record (EHR) software makes use of APIs. So individual patients and their healthcare workers would be end users using the EHR software. Fintech budgeting or lending apps might make use of APIs. So again individual households, or SMEs might use these apps. |

|

| End users (for example: Researchers and Academia, Media) | Some end user populations may use the data or services from APIs more directly but not be consumers who are directly interacting with the API. For example, some researchers and media might use a workflow automation tool, spreadsheet or BI tool that has already integrated an API in order for them to access the data being connected. | Number of researchers/media making use of data provided via API. Tools available that have pre-integrated an API for end users. |

| Indirect beneficiaries (Society, Economy, Environment) | The goal of APIs and API-related infrastructures in an open ecosystem is to enable everyone to participate and co-create their own value. This is reflected in some regulatory goals: for example open banking goals often stipulate that a goal of open banking is to provide greater consumer choice. In open health, goals often relate to minimising the amount of repeat data that patients must provide to each healthcare professional, or to reduce risks of contraindications of medications or therapies where the full range of therapies being prescribed is not known or checked by healthcare professionals, and so on. Ideally open ecosystems should also reduce the impact of traditional imbalances of power, for example, women-owned businesses do not receive business financing in line with the experiences of their male counterparts. Tracking the societal impacts of open ecosystems can monitor these wider, indirect impacts. Similarly, the growth of new startups operating that make use of APIs and data should stimulate local economies. And the use of APIs and data should lead to more efficient resource use and less waste. For example, trip planner and route planner APIs can reduce carbon emissions from travel and local transport by providing more direct travel routes. Reported improvements in convenience and reduction in waiting times to carry out administrative functions. |

|

Defining the size of the ecosystem to be analysed

The model could also be used to describe:

- A specific geography's ecosystem (for example, all stakeholders operating in a particular country for a given industry ecosystem)

- An industry sub-sector or lens within a wider ecosystem (for example, in open health, it could describe all stakeholders working in a specific burden of disease like cancer or breast cancer, or for a specific sub-sector like medical devices, or a combination of sub-sector and geography, for example, all medical device stakeholders operating in a specific country)

- A specific organisation or business platform's own ecosystem (for example, all stakeholders in an API aggregator's ecosystem).

Using ecosystem models to analyse and take action

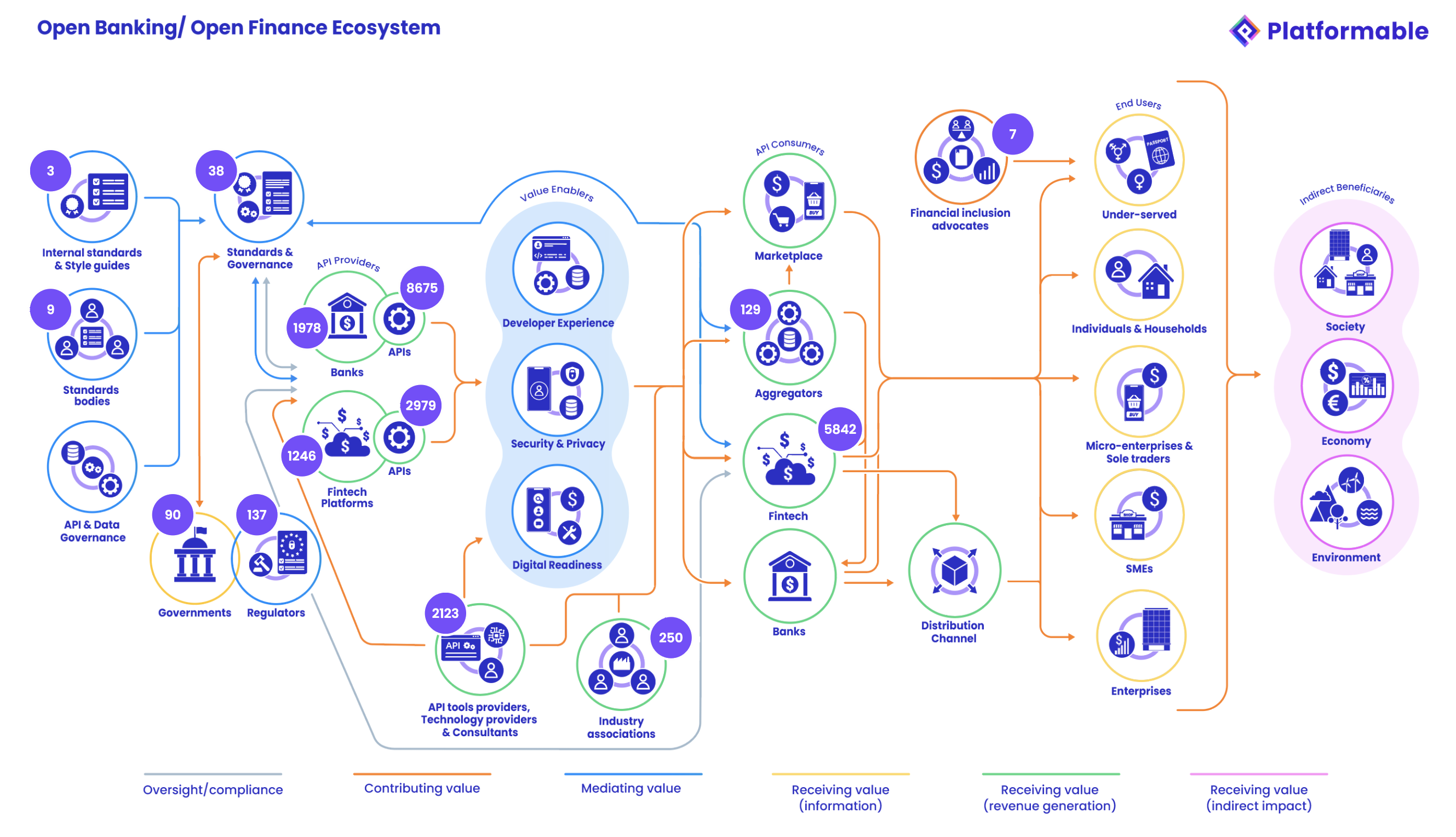

At the highest level, the ecosystem map may be a diagram with key indicators shown, like we use in our open banking/open finance quarterly trends reports:

Ecosystem analysts could then drill down into specific areas they would like to investigate. For example, from this open banking diagram, perhaps if you drill down into regulations, you can see where all of the regulations exist:

This could go even further to provide filters such as looking only at those regulations that are implemented and have a goal of financial inclusion (we count 11 core open banking regulations globally that specifically include financial inclusion as a goal):

The big advantage of this approach to ecosystem modelling is that analysts can start from anywhere on the map. Too often, new initiatives start by looking at who else got investment. Instead, this ecosystem can start by looking at gaps and needs: areas where there are large enough (viable market) populations facing specific needs, and then look at who is providing services and products to those populations. Where it is decided that there are not enough solutions, that could be an area of focus for new startups or existing businesses looking to expand their product range. Again, existing ecosystem models don't offer that lens. Several years ago, investors were more willing to invest in early stage startups to see what gained traction, and were more speculative in their investment choices, which distorted ecosystem maps in one direction to show a proliferation of products that had no real use case or need. Now, investment continues to narrow and select more mature and less-risky startups, so ecosystem maps based predominantly on emerging investment distort the ecosystem view in a different direction but still aren’t truly indicative of ecosystem stakeholder needs and activities.

Elevating data collection and availability to map ecosystem stakeholder needs (rather than just listing startups and businesses operating in the ecosystem), also helps re-centre customer data away from an over-reliance on an individual business' collection of personal customer data as a source of knowledge about customer future preferences and needs. Instead, customer relationship management (CRM)-collected data can be included by an individual business but alongside other sources that show normative, expressed, felt and comparative need of customers/end users/populations in a way that does not reinforce data surveillance or promote intrusive personal data collection and storage.1

This data collection for analysing open ecosystems could also be used to train language models on the open ecosystem and possibly help build AI tools to analyse opportunities and gaps faster and with a local context or specific lens applied.

In more complex areas like climate action and health pandemic response, it is essential to understand who is available to partner with and what they are working on, what data and API services they have to integrate with and so on. Again, this ecosystem model can help with identifying those potential future partners.

Before entering an existing ecosystem, an organisation can review what standards and data models and regulations govern that ecosystem to ensure they are prepared and able to work with existing ecosystem stakeholders. This can also help with entry into new markets for existing players: analysing the ecosystem maps at a geographic level can help an organisation look for low hanging fruit where the organisation can first select new markets that have a similar regulatory context and use existing standards and data models used by the organisation.

2024: The year for analysing open ecosystems

The open banking and open health experiments in open ecosystems have proven successful enough that there is great interest in replicating these models for other areas of global digital infrastructure. The United Nations Environmental Program is building out a global data digital infrastructure that will hopefully take an open ecosystem approach. Ports and airports are building on open APIs to create open ecosystems for logistics and travel. There are moves in global trade, intellectual property, manufacturing, smart home and facilities automation, and so on that will progress rapidly in 2024. A greater involvement by regulators (as has been seen with AI and data sharing more generally), and increased interest in interoperability also point to the potential growth of open ecosystems in the year ahead.

As we have seen in previous waves that moved from project to product-centric approaches, and from APIs to product APIs, 2024 will also see a move for some from product manager to ecosystem manager. In other cases, leads responsible for innovation or partnerships will become ecosystem managers, or facilitators. (We are already seeing an increasing number of 'Global Alliance' roles emerging that will take on some aspects of the ecosystem manager role.) It's a role that the folks at data.org are referring to as the "Data Ecosystem Designer". They note that such a role would require skills and experience in data governance, technology, and product development with a mindset for partnerships, ability to consider local context adaptation, an appetite for risk, and the ability to switch hats and be able to have technical and product-specific conversations beyond a mere surface level. While they focus on the role for analysing ecosystems around digital public goods, we think the ideas are just as relevant for open ecosystems.

At Platformable, we believe our ecosystem modelling approach would help these ecosystem designer roles to dig deep into understanding the various components, stakeholders, challenges, and opportunities. Since the model monitors how value is generated and flows through an ecosystem, it is also ideal to use as an operational framework when setting and collecting impact metrics. Over time, it will be possible for ecosystem designers to better strategise where to focus their organisation's attention in order to strengthen impact and deliver outcomes (or revenue streams for for-profit businesses), or to build AI tools that might help with initial analysis prior to a deep dive into strategy opportunities.

2024 will see greater interest in moving away from existing investment-based, stakeholder directory lists as a means of describing an ecosystem, to models along the lines of what we have created at Platformable. Currently, we use our models to generate industry trends reports and are working on dashboard tools to allow this new approach to ecosystem analysis. Please reach out if you have ideas, would like to be involved in focus testing, or if you want to test our model by mapping your organisation's ecosystem.

Article references

Mark Boyd

DIRECTORmark@platformable.com