Understand

Data justice principles at the core of a health data governance framework (Data Governance for Digital Health Ecosystems 2)

Data Justice at the core of a Health Data Governance Framework

The concept of data justice has been evolving and increasingly gaining recognition in health data governance circles (and in wider data governance efforts).

At Platformable, we tend to use the definition published by the Royal Roads University.

For decades now, Indigenous people, and leaders across Latin America and Africa have been advocating for better representation when data about their communities is analysed. The term "data justice" has emerged from this advocacy work and dates back to 2017 when Linnet Taylor first proposed its definition:3

The term started gaining traction initially in climate, agrifood, and sustainability sectors, in data governance circles, and is now increasingly referenced in digital health.

Current research

A current, multiyear study being undertaken by Sharifah Sekalala and James Shaw4 looks to advance health data justice by comparing how the concept aligns with health data governance frameworks and models in Canada, Germany and the UK.

In a 2023 piece by Shaw and Sekalala published in Nature's NPJ Digital Medicine4, the authors describe data justice as "a group of frameworks informing the study and use of data in ways that prioritize the needs and experiences of structurally marginalized communities, and contribute to efforts to redress structural, institutional, and political injustices."

They note two key features of data justice are that:

The study commenced earlier this year and is expected to conclude in 20285.

Data justice vs patient-centred care

In the development of digital health solutions and services, many are familiar with the idea of patient-centred design. In the latest round of country-level digital health strategies (that is, those from the past few years and that are generally guiding governments til, say, 2027 or 2028 depending on the country's strategic cycle), we have noticed a greater shift towards situating policy and strategic action around "the patient at the centre". But this is often akin to a user experience mindset where data is used to identify patient needs. Feedback mechanisms are put in place to allow patients to rate and provide comment on service quality from using digital health solutions in their instances of care, or along their care pathway.

This patient-centred model then informs the design of health services at the provider level, and sets research priorities for healthtech and innovators when building solutions. Some organisation's even establish their data governance framework to align with their country's digital health strategies and, as a result, their frameworks focus on people-centred user experience approaches that avoid methods that would involve the patient and community as more active participants — partners — rather than as recipients of health care.

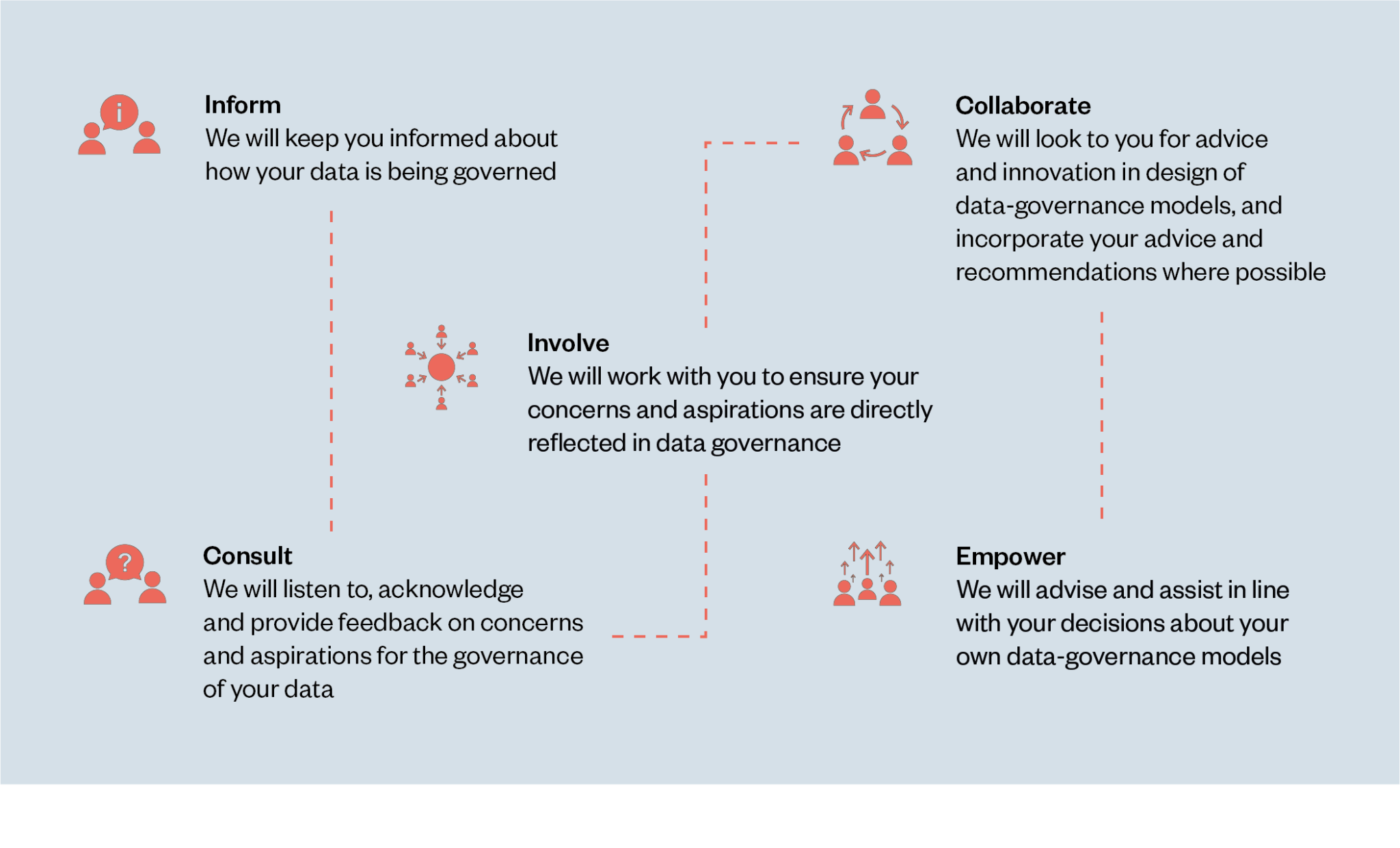

Drawing on seminal work in urban planning research by Sherry Arnstein6, the Ada Lovelace Institute7 produced a study on participatory data stewardship that describes the limitations of this user experience research model if applied to data governance efforts, and this is equally relevant to health data governance, of course:

Rather than starting from a definition of patient-centredness drawn from a country's digital health strategy, your organisation is better placed to take the time to think about your own mission statement, role, and values, and set guiding principles for data governance in that wider context.

When building your health data governance framework, such as when developing policies and mapping regulatory and compliance requirements, you can make sure you align with the national and local strategic priorities, when thinking through what patient-first focus means for your organisation.8 But we would argue your health data governance framework should start from a consideration of your organisation's mission not the national digital health strategy where you operate.

Defining your own principles

As part of our framework, you will work on your data governance policies and processes. These will inform the actions and activities you undertake to manage data across the data lifecycle. Your policies are informed by your overarching principles.

We argue in our framework that data justice must be reflected in your core principles that will guide your whole organisational approach.

Data justice is important from a community point of view, but it is equally as essential from a commercial and innovation standpoint.

From a community point of view, data should not be analysed for any individual without their participation. People's rights should not be impacted by the weaponising or use of data in ways that limit participation in society, remove or deny access to human rights, or that increase negative health outcomes at the individual or population level.

From a local economy point of view, if people do not trust sharing health data with organisations, they may avoid seeking healthcare which can contribute to greater economic burdens such as higher acute care, and potential long term disability, costs, less workforce engagement (from patients and their carers), or the spread of communicable diseases.

From a commercial point of view, digital health ecosystems rely on the sharing and use of data. Data sharing requires all stakeholders to trust how the data will be stored, used, shared, and analysed. Patients will not consent to sharing their data if they believe it will be used maliciously or in ways that could harm them, or if the benefits of sharing are not shared widely.

Some countries face challenges in encouraging healthtech innovation by commercial partners because the citizen population has a high perception that those wishing to use data for research or other purposes are not trustworthy or that the benefits will not flow back to themselves or the wider population.9

In addition, healthtech are more likely to succeed with less iterative designs if they build digital solutions in partnership with users, and can demonstrate robust security and ethical and responsible data use.

Drawing on existing principles and frameworks

In our overview article, we referenced four possible data justice frameworks that can be drawn from when defining your organisation's core principles:

Transform Health principles

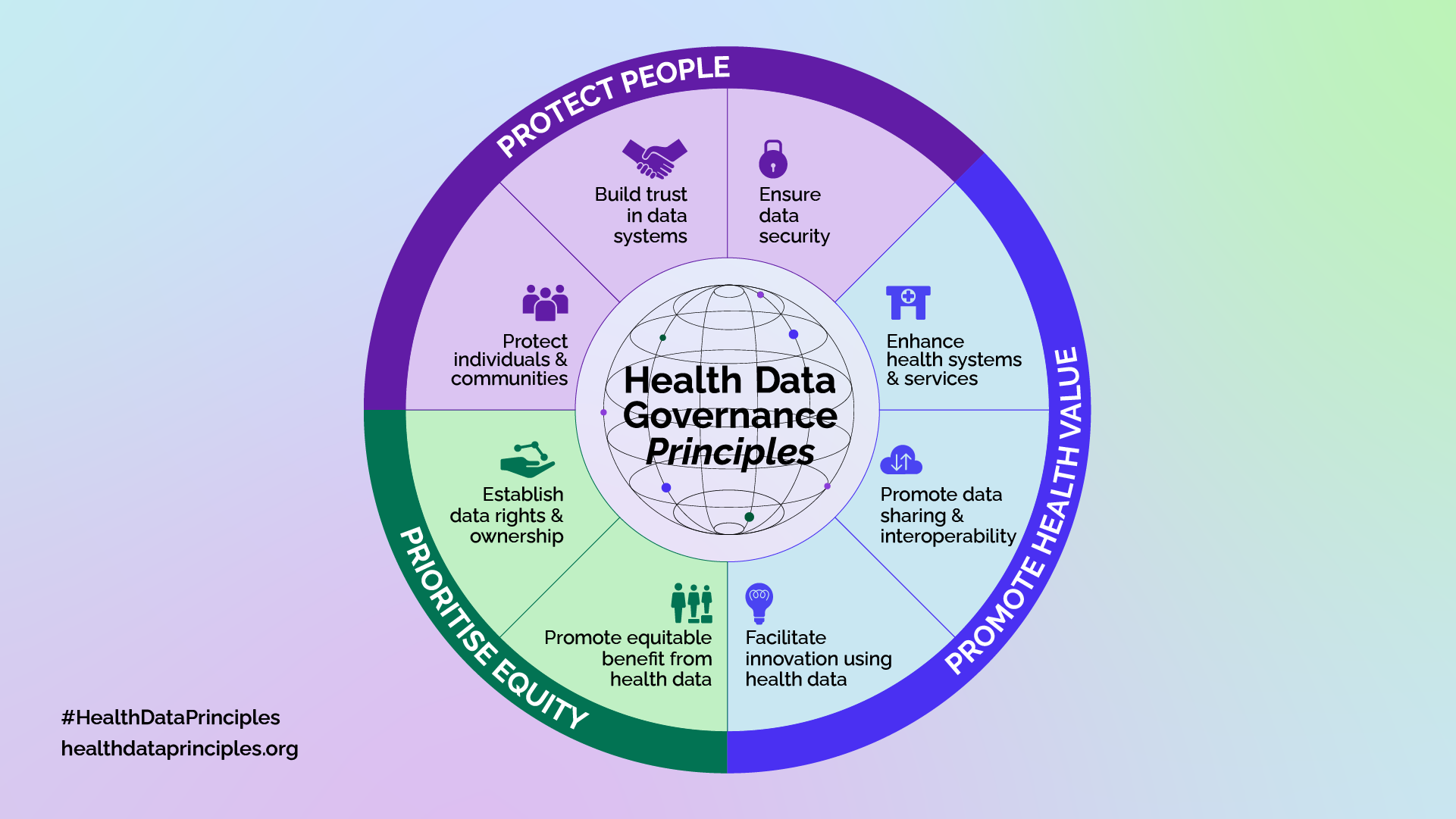

Platformable is a signatory to Transform Health's Health Data Governance Principles.

The three key areas that are critical to protecting people in developing a health data governance model include:

Protect People

Data policy, which includes alignment with the various laws and regulations that establish the norms for how data should be collected, stored, and used, is a key piece of an organisation's data governance model. In particular with health data, proper data protection practices are even more critical due to the sensitive nature of health data, and often require adherence to additional protection and regulations.

Health data that is unprotected, at both an aggregate or individual level, can be misused by various bad actors, harming individuals, groups, and communities, including marginalised and high-risk populations. The development of special measures to protect against both collective and individual harm, including the exploitation, discrimination, and harassment of people sharing health data with organisations is fundamental to health data governance frameworks.

The three key considerations in protecting people are:

Promote Health Value

Perhaps the key purpose of health data governance is to enable the use of health data to improve the health and well-being of the individuals that an organisation serves. Health data governance practices should always strive to obtain the maximum value from the collection, use, and analysis of data to improve health outcomes at both individual and societal levels. To achieve this goal, organisations often must share some or all forms of health data that they collect. Siloed data can negatively impact the value that such data can create when combined and aggregated with other available health data and information. Data sharing and aggregation must be done in a manner consistent with the protection of individuals, groups, and communities and their rights.

Health data governance also promotes innovation. The use and analysis of data can often lead to the development of new health services, health therapies and treatments, medical devices, community-based interventions and health promotion activities, or improve existing ways in which the health sector impacts individuals.

The three key considerations in promoting health value are:

Prioritise Equity

It is important that any value created from the collection and use of data must equitably benefit the individuals and communities from which the data originated.

In establishing a health equity approach in the development of a health data governance model, organisations should consider the following two aspects:

These guiding principles of protecting people, promoting health value, and prioritising equity are core to the Platformable Data Governance framework and will be a common theme throughout this blog post series.

First Nation's OCAP Principles

The First Nation Information Governance Centre describes the OCAP principles:10

FAIR & CARE

The FAIR guiding principles11 stipulate that data should be:

These principles are then used to guide data governance efforts, but they do not address any of the data justice issues described above. Thanks to the leadership of Indigenous communities around the world, the FAIR model was extended to include CARE principles12 in which community ownership and involvement were included alongside the FAIR approach. The CARE principles recognise:

While designed to ensure Indigenous rights over data management, they are a gift from First Nations Peoples to non-Indigenous communities who can also draw on these well-articulated principles when considering how data should be managed for any community or community member.

Patient-Centred Care and Participatory Models

There are some patient-centred care models that extend beyond user experience-informed principles to incorporate more participatory principles.

For example, Datalabe works in Brazil with residents living in favelas and peripheral areas to assist local community members to define data systems and build data collection instruments.13 These approaches, built on core data justice principles, often have a health focus like their community-led studies into fresh water supply and sanitation services.14

The Access to Health and Rights Development Initiative (AHRDI) in Nigeria takes a similar approach in their community-led data advocacy projects.15

The study and resulting index by Maaß, Rothgang, Zeeb, and Shüz (2024), Multidisciplinary measuring of maturity and readiness in national digital public health systems: The digital public health maturity index,16 proposes several indicators that can measure digital health maturity through enabling participation. These indicators could help inform thinking around what principles to articulate in a data justice approach. These maturity indicators are scored on a scale where highest maturity is calculated when there is end user involvement through participatory approaches at all stages in response to the following:

Some national health strategies do show participatory mechanisms informed from data justice principles in their documents. France's Global Health Strategy, for example, describes a core focus goal:

The Irish Digital Health Strategy (Digital for Care — A Digital Health Framework for Ireland 2024-2030) is also built on citizen empowerment principles, including "Patient involvement" which is described as:

Challenges with data ownership models

Current debates around genomic data raise particular data ownership issues, as described by Nielsen & Nicol,17 which appears to have been published around the same time as the WHO guidance on human genome collection, use and sharing.18

One issue that is touched on in these documents is the challenges of individual ownership over data that often reflects or could be used to assess another member of the data sharer's family. Who should be involved in decisions about how that data is used? The individual or the extended family?

There are a range of other community-level data ownership challenges beyond genomic data: even if data is individually collected and used responsibly, if aggregated data is then used to describe a community, how does the community have a say in how the data represents them?

If data is used to generate commercial advantage or academic prestige, how is this value shared with the data contributor? This imbalance occurs at the individual level but also amongst digital health ecosystem stakeholders, particularly in global research studies, where researchers from the Global Majority will share data with researchers in, say, Europe, and their data is used for research that they don't end up getting invited to do with their European counterparts, at times not even accredited for their data contributions. This issue was highlighted in our study with the ODI for WHO on data governance maturity.

Challenges with consent models and opt-in and opt-out approaches

As we work across a range of regulated industries, we get to see how issues of data ownership are dealt with in other sectors and can learn from best practices.

In open banking/open finance, for example, regulations have set rules around banks needing to allow customers to decide on how their bank account information can be shared, so that they can make it available in budgeting and financial health monitoring apps, to analyse their expenditures against their greenhouse gas emissions to assist in changing their behaviour, to use in wealth management and investment decisions, and in sharing with potential credit and financing providers. There are even use cases where customers are sharing their financial account information data with landlords to demonstrate their reliability as tenants.

In Europe, the Third Payment Services Directive and related regulations around instant payments and digital wallets require financial services providers to offer a dashboard where customers can see which entities they have shared their data with and be able to revoke permissions at any time.

Work we did with World Bank on explaining consent workflows was also aimed at financial service providers in low and middle income countries to build digital literacy and ensure consumers understood how they were permitting access.

In banking/finance it is a little easier for customers to manage their consent at a granular level, although the focus hides some of the data justice questions particularly around how communities are involved when aggregated customer data is used to predict insurance premiums, loan application risks, and so on. There are no clear data justice models to involve local communities in how that data is used.

But there is a lot of potential in consent dashboards for health data. We argue in health, there needs to be a continuous consent/continuous engagement cycle, as shown in the diagram below. (We will come back to this in our data policy post.)

Other sectors such as sustainability have also looked at improving consent as a first step towards data justice. The industry body for sustainability standards organisations, ISEAL, has excellent guidance that is regular referenced across the whole sustainability industry.

Individual consent is one step in data, but consent also needs to be managed at a community and population-level, especially when citizens are opted in to automatically share their data unless they request otherwise. This can make sense: no one likes those cookie consent forms where you have to toggle off all of the "legitimate vendors" (how can there honestly be 47 legitimate vendors you need to consent to for sharing internet website visit data to 'measure advertising performance', as one of a whole range of data use cases any time you read a news article online?!). Having a similar process for sharing health data would be a barrier to anyone sharing data for health research. But a consent dashboard would allow health data sharers to see whether there were any impacts from their opt-in or selected data sharing: gaining news of new research or population benefits their data sharing helped generate, or being alerted to data breaches they may not have been aware of, for example.

As part of a data justice approach to population-level consent sharing of health data, the UK has established the Confidentiality Advisory Group which sets rules around non-consented access to health data for research purposes. According to Connected By Data: "An academic analysis of CAG minutes suggests the Group expects patient involvement and engagement work to be embedded (present throughout the research cycle), evidenced (explicit in the application), targeted (specific to the project and discussed with likely data subjects) and accessible (information sensitively provided for all users).19

Another study by Connected By Data and Just Treatment in 2023 is still relevant, and it is concerning that the issues raised in that report have not been addressed by the current UK government, which has shared health data with private companies like Palantir, most recently through a 330 million GBP contract20 with the US spy and surveillance tech agency. (Demonstrating our above discussion on how poor data justice principles can impact on commercial initiatives, a Manchester-based health board has deferred adoption of the health data services using Palantir.)21

Regarding consent, Connected By Data recommended:

Data justice in the age of AI

Data justice principles and digital literacy around data ownership and participation need to be rapidly advanced to address how patient data and communities are involved in decisions around data when AI use cases are implemented.

Governments, healthcare providers, and others appear to be rapidly adopting AI for healthcare use cases, but structures that ensure patient and community participation in how data is used by AI is not in place.

For example, we have heard that some diagnostic AI instruments rely on open source skin imagery libraries that are predominantly of white patients, meaning AI-led diagnoses are likely to under-report skin cancer risks for non-white populations. It does not appear that there are structural mechanisms to ensure patient communities oversee how AI is being used, nor what data models have been used to train those models. The European AI Act requires transparency around the data used to train models, but there is still much work to be done on ensuring that happens in health, and on implementing suitable explainability actions.

The lack of governance processes over datasets that are likely to be used for AI is another issue. If communities share their data and expect it to be shared for population health benefits, are they involved in (or aware of) decisions around how that data is provided across the ecosystem? Our understanding, thanks to Dr Emma Hodcroft raising the issue, is that GISAID, a key data source for tracking pandemics and identifying COVID variants is limiting access to data to other researchers and tools providers.

This is especially concerning as the first case of human transmission of the H5N5 avian flu virus has now occurred.22

Applying data justice throughout the health data governance framework

Defining data justice principles that apply to all data governance efforts will be essential when then working through maturing your health data governance framework using our model components. This post has raised a number of issues that can be considered when defining your principles.

To move forward, you can:

- Review your mission statement and values

- Review the data governance principles frameworks described above

- Generate a set of guidfing principles for your data governance framework based on your mission and values and existing data justice principles

- Refine your draft principles as you consider the issues raised throughout this post on consent, community participation, and AI.

Of course, take these actions in partnership with stakeholders and the communities you serve. We will also discuss data justice at each stage of the data governance framework to see how these principles translate into action as you manage health data.

Article references

Located on the traditional Lands of the Lekwungen-speaking Peoples, the Songhees and Esquimalt Nations in Canada

Royal Roads University (2025). Data justice. Cited at: https://libguides.royalroads.ca/datajustice

Taylor, L. (2017). What is data justice? The case for connecting digital rights and freedoms globally. Big Data & Society, 4(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951717736335 (Original work published 2017)

Shaw, J., & Sekalala, S. (2023) Health data justice: building new norms for health data governance. npj Digit. Med. 6, 30. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-023-00780-4

Arnstein, S. (1969). ‘A Ladder of Citizen Participation’. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), pp.216-224. Available at:

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01944366908977225

Ada Lovelace Institute (2021). Participatory data stewardship. Available at: https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/participatory-data-stewardship/

You can certainly use national strategies as inspiration (this article will share examples from national digital policies in Ireland, Brazil and France, for example).

The Roche Canada report on a connected health data system notes the Canadian population's distrust in sharing health data. Local UK regions and hospital networks are deferring use of health platforms due to concerns around data sharing with Palantir.

This section was quoted from: https://fnigc.ca/ocap-training/

As described by GO FAIR at: https://www.go-fair.org/fair-principles/

As discussed at https://www.gida-global.org/care

See https://datalabe.org/lab-cidadao-a-metodologia-do-cocozap-em-outros-territorios/

See the Documenting Human Rights Violations project as an example: https://ahrdi.org/projects

Maaß, Rothgang, Zeeb, and Shüz (2024), Multidisciplinary measuring of maturity and readiness in national digital public health systems: The digital public health maturity index. Available at: https://media.suub.uni-bremen.de/entities/publication/64e30e7e-14c1-4561-bf38-c4d3a1a9689a

Nielsen, J. & Nicol, D. (2024). Data ownership in genomic research consortia, Journal of Law and the Biosciences, Volume 11, Issue 2, July-December 2024, lsae024. Cited at: https://doi.org/10.1093/jlb/lsae024

WHO (2024). Guidance for human genome data collection, access, use and sharing. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Cited at at https://iris.who.int/server/api/core/bitstreams/c32ba78e-de45-416a-a5ae-3863b93e4628/content

Freeguard, G. (2025). How can we ensure public data is shared in the public interest? Available at: https://connectedbydata.org/resources/case-study-cag

Marr, A. (2025). The Palantir problem. Cited at: https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/health/2025/03/palantir-problem-nhs-andrew-marr

Clark, L. (2025). Manchester hits snooze again on joining Palantir-run NHS data platform. Cited at: https://www.theregister.com/2025/11/20/manchester_nhs_fdp_deferred/

Washington State Department of Health (2025). H5N5 Avian influenza confirmed in Grays Harbor County resident. Cited at: https://doh.wa.gov/newsroom/h5n5-avian-influenza-confirmed-grays-harbor-county-resident

Mark Boyd

DIRECTORmark@platformable.com

Eric Rochman

EXTERNAL PARTNER