Engage

Open Banking and Open Finance Regulations as at Q1 2024

Open Banking regulations continue to be introduced across the world, with keen interest from countries looking at the various successful implementations, such as in the UK, Europe, Australia and Brazil.

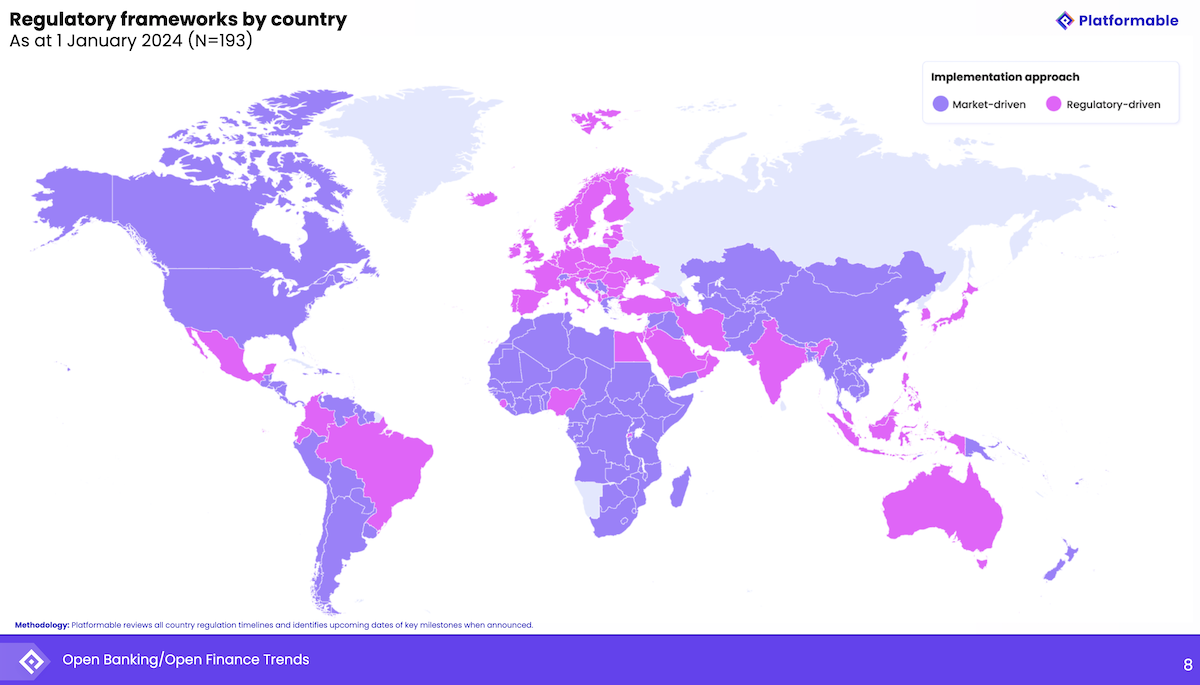

69 countries currently have implemented some stage of open banking regulations (including one that is currently stalled). There are a further 18 countries with a current market-driven approach at various stages of discussion towards a regulatory framework, including the United States which has recently introduced new proposals to consider financial data sharing and portability, and in Switzerland, where the Federal Department of Finance announced that, this year, measures will be imposed against institutions that fail to make data available to TPPs (third-party providers).

In countries where regulators seek to promote open banking or open finance models, goals should be clearly defined. In 26 countries, the promotion of competition and/or innovation are the main goals given, but often other goals that reflect the economic and social context of the region or country are included. For example, increasing financial inclusion is a goal that makes sense in low- and middle-income countries and regions where there is a predominantly underbanked population (13 countries stipulate financial inclusion as one of the goals of their open banking regulation), while higher income countries tend more towards focused on “financial health of consumers” (31 countries have included this as a goal).

124 countries have a market-driven approach to open banking, that is, individual banks and fintech providers could make use of APIs if they so desired, as long as they meet more general financial data and service regulations (such as data protection regulations generally if they exist, or anti-money laundering, or payment institution regulations and so on).

Market-driven countries include those where there may be an active data exchange and lack of a regulatory framework, but also those where we have not identified any impediment that would prevent innovators from building solutions based on data exchange. As such, some of these markets are more active than others. In some regions, market-driven open banking and open finance stakeholders include telecommunications carriers that may offer digital wallets, initially introduced to allow pay-as-you-go of mobile phone services but increasingly used as a digital money wallet allowing payments to sole traders and to transfer money through telco agent branches across a country.

There are also currently 43 countries at various stages of adopting an open finance regulation.

Standards as a key driver in any regulatory environment

The regulatory and market driven approach and its benefits or disadvantages depends on the practices and the context of each country, although it appears that having a standard, either prescribed by government regulators or industry-adopted is a key driver in open banking adoption.

For example, in the UK, when the obligation to share data began in 2018 and an API standard was introduced, 1.2 million API calls/month were registered. By the end of 2023, 1.3 billion API calls/month have been exceeded1.

In a market-driven context, North America, with thanks to an industry-led effort, the API standard, FDX, has been widely adopted. They now report that 65 million consumer accounts are already using services that are powered by APIs that make use of their standards.

Whichever regulatory approach is chosen, implementation must arise from a collaborative effort between the public and private sectors to implement standards wherever possible to ensure data exchange is interoperable.

Some countries have learned from international experience and have incorporated certain aspects into their frameworks. For example, as Europe reviews its Second Payment Systems Directive (PSD2) discussion for a proposed PSD3 legislative package draws on the successes of the UK’s approach in relation to creating an API standard rather than providing guidelines which led to the complexity of each bank creating their own approach to building mandatory APIs.

Some countries are also thinking through the future potential of data exchange, taking the opening of data beyond an open banking regulatory framework for bank accounts and payments and even beyond the financial sector. Australia and India, for example, are looking at how data exchange facilitates a wider open economy, where data is shared in sectors including telecommunications, energy, and agriculture.

Two future challenges: Funding and analytics

Going forward, one challenge for many countries will be the financing of new open banking regulatory regimes. Having a central structure that manages all aspects that have to do with the onboarding of TPPs and the issuance of their authentication certificates, as well as the management and maintenance of the API standards is admirable and has advantages, but the costs of managing such a new administration is facing some challenges, particularly in the UK. In the case of the UK, the financing costs were borne by the Open Banking Implementation Entity (OBIE), funded by the nine banks obliged to open data, while in Brazil the private sector committed to establishing the Convention. In other countries, it is the authorities that are in charge of developing and publishing their standards or rules, as is the case in Mexico, where four financial authorities are responsible for the regulations and standards that will apply to their supervised sectors.

One shortcoming in current moves towards open banking regulations globally is the limited availability of data analysing the impacts that the new regulations are having on the country. While UK and Brazil provide data on the number of API calls being made on a monthly basis, and each calculate the number of consumers making use of open banking services (albeit in different ways), a well thought-out analytics and reporting structure in any country that aligns metrics on impacts against the intended goals of the regulation is missing2. Metrics on the improvement in consumer choice, reduction in fees paid for financial services, increase in financial health, protection and breaches of data privacy, reduction in financial exclusion, growth of the financial services sector and its local economic impacts, and so on could all be generated from open banking analytics reporting but are not yet sufficiently developed in any jurisdiction.

Article references

UK API calls data from https://www.openbanking.org.uk/api-performance/

We find the UK Open Banking Limited approach to analytics and reporting the most encouraging. As we discuss in our data governance models, the UK has identified their theory of change for what the regulation goals intend to generate, which helps guide their data collection and reporting: https://openbanking.foleon.com/live-publications/the-open-banking-impact-report-october-2023/cef-theory-of-change-model Our biggest shortcoming with their approach is that it relies heavily on surveys for many data points when the open banking ecosystem could generate this data automatically with a few specific additions to how data is collected.

Mariana Velázquez

SENIOR ANALYSTmariana@platformable.com