Engage

Global digital health policy maturity assessment indicators

Governments around the world are beginning to enact digital health policies that aim to modernise health systems, enable greater use of data, and encourage innovation to improve population health and wellbeing, reduce health inequalities, optimise health services resources, and empower industries and academics.

Our experience working in public and digital health

At Platformable, we have been working in this field for years:

- As founder and Director at Platformable, this work is an extension of work I have been involved in throughout my career. I helped established patient representative organisations and networks for the people living with HIV/AIDS movement during the AIDS crisis in the 1990s in Australia where we used data and research to guide national and state health and anti-discrimination policies; I designed population health and wellbeing data systems for local governments and state-based health inequalities data mapping frameworks

- We have worked with NGOs and corporations on implementing health data governance best practices

- For the UK's Open Data Institute and Roche, we prepared data governance resources including playbooks and workshops, conducted studies into digital health policy and health data ecosystem development across Europe and neighbouring countries and for the Western Balkans; and for the World Health Organisation, we conducted studies in health data governance maturity and mapped digital health ecosystems

- I speak regularly at national and international conferences across Europe and the Western Balkans, Brazil, Canada, and the UK on digital health policy maturity and comparative approaches

- For Roche Canada, we mapped digital health regulations, policy and health data interoperability across Canada's ten provinces and nationally, which we are now preparing to release as an interactive website.

Building towards a set of health policy maturity indicators

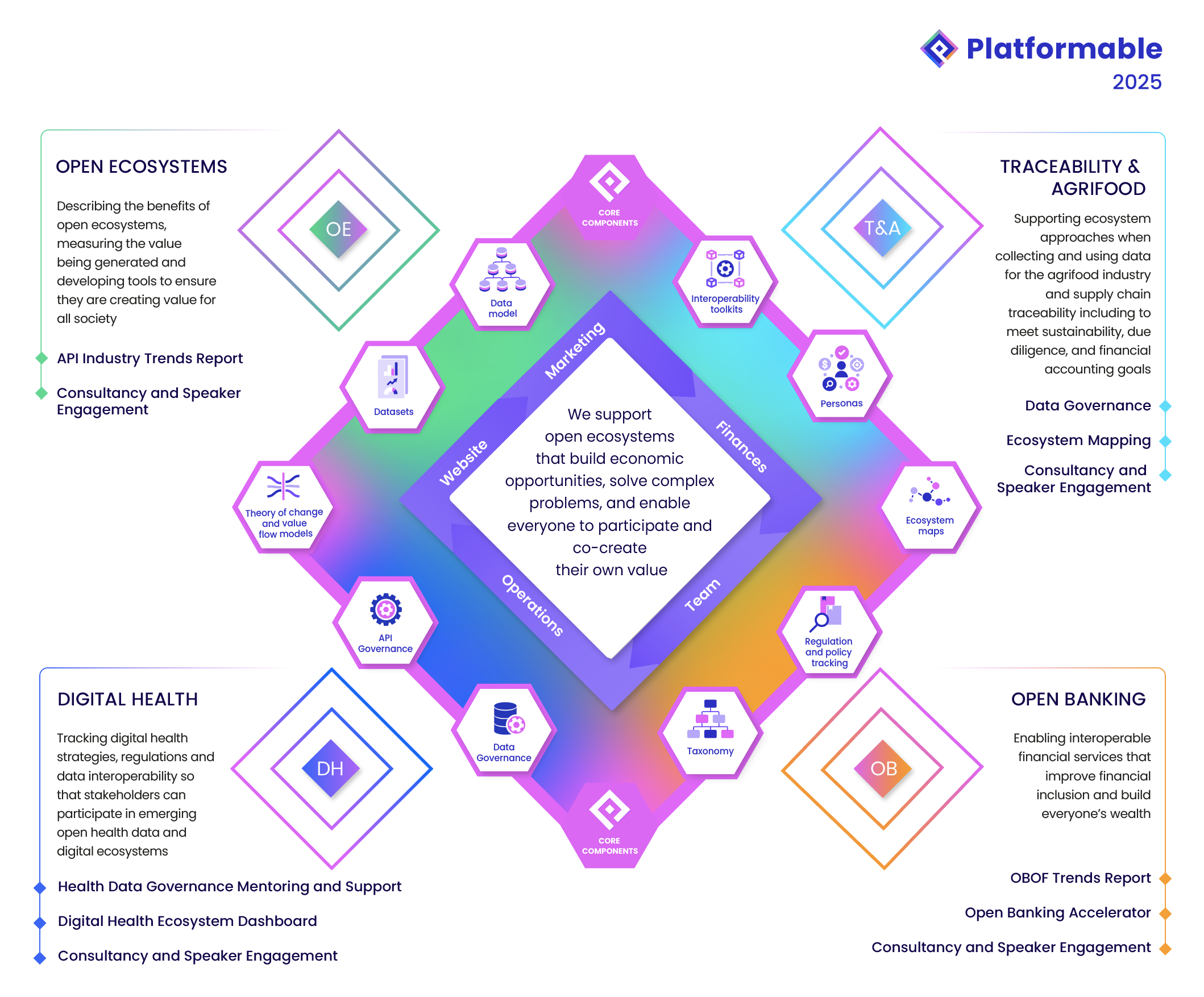

At Platformable, our mission is to support the development of open digital ecosystems. We draw on a range of methodologies, techniques and core building blocks to do this, as shown in the following diagram that describes our work at Platformable.

For digital health, some of our core building blocks include:

- A mapping of the digital health ecosystem that can be applied at a geographical, burden of disease, or therapy/intervention level (see the final section of this article)

- A Health Data Governance framework

- A core set of indicators that measure the maturity of a digital health ecosystem.

If you are seeking to collaborate with others or provide health-related digital products and services (or digital products and services to health ecosystem stakeholders), it is important to understand the level of maturity of the digital health policy environment at a geographic level, or at a burden of disease level, or within a specific therapeutic or intervention modality in order to decide how to participate in the local ecosystem.

Starting with ehealth: electronic health record digitisation and use

The conversations around digital health policy are still in a nascent phase. During our study in 2023 on the digital health policy maturity in the Western Balkans, we made the distinction between ehealth and digital health strategies. We see ehealth strategies as strategies that focus on healthcare modernisation and interoperability for primary use of data, that is, to enable greater use of digital systems and data to support direct healthcare service delivery. This important phase ensures that electronic health records infrastructure is put in place, that patients can consent to their data being shared across their healthcare team (for example, from a hospital surgeon back to their GP), that online bookings and appointments can be made, that patients can access their diagnostic reports, and that pharmaceutical records are managed electronically, amongst other digital enablements.

Electronic health features accessible to patients: patient portal features

Patient portals linked to individual electronic health records are becoming mainstream, although there is still wide variability in what features are available in each country and each state/province within a country (where health services management is federated). Further research into the benefits of patient portals and digital access to health records is also needed. A good systematic review was last done in 2021, which I would consider out of date now, given the advances over the past years and the fact that the wider population is more digital savvy than even five years ago (and post-COVID make more use of digital health services). However, at that time, patient portals were demonstrated to improve patient-health care provider relationships, improve health status awareness, and increase self-management of health solutions. Data was less clear on whether health service access or efficiency were improved at that time1.

To create a full list of possible patient-facing ehealth features we drew on a range of sources:

- A systematic review of classification features of patient portals which we generally followed1

- A study into personal health records2 which is now a little out of date from 2021

- Our own analysis of features available on patient portals across Canada that we conducted for a study on health data interoperability in Canada.

Our list includes the following:

| Patient portal features |

|---|

| Electronic referrals |

| Electronic health event or medical record summaries |

| Diagnostic test results |

| Care plan management |

| Appointment booking and management |

| Medications management and e-prescriptions |

| Chronic disease management/ health information resources |

| Telemedicine (telehealth) and mobile health (mHealth) |

| Vaccine/immunisation data |

| Ability to integrate personal health device data |

When assessing a digital health strategy's maturity in terms of ehealth objectives, we wanted to look at overall continued investment in digitisation for primary health data use, which we measure by whether there is continued investment in providing these data access features to patients.

Moving beyond ehealth to digital health

In our opinion, a digital health strategy goes further than this: a digital health strategy focuses on maintaining and advancing that ehealth modernisation strategy, but has an additional focus on enabling secondary use of health data, that is, combining this health data with other health and social determinants data and creating a responsible and ethical data governance framework that enables this data to be used for research, personalised healthcare, improved healthcare services planning and management, health technology assessment, fostering health innovation hubs, health outcomes reimbursement financing models, and so on3.

Defining digital health

At Platformable, we needed a definition to describe how we see digital health.

WHO uses the definition:

"The field of knowledge and practice associated with the development and use of digital technologies to improve health. Digital health expands the concept of eHealth to include digital consumers, with a wider range of smart devices and connected equipment."4

Australia uses the definition:

Digital health involves "supporting a modern, high-quality health system, improving the quality of life of individuals, families and communities, and equipping people to confidently manage their health and wellbeing journey. It’s also about enabling healthcare providers to maximise their skills and contributions by increasing effectiveness and efficiency. Digital health is the foundation for all modern health service delivery and should improve safety, quality, productivity and efficiency."5

A study on digital health definitions6 found the most common elements would suggest a definition that recognises that "digital health is about the proper use of technology for improving the health and wellbeing of people at individual and population levels, as well as enhancing the care of patients through intelligent processing of clinical and genetic data."

OECD use this definition7:

"The field of knowledge and practice associated with the development and use of health data and digital technologies to improve health. Digital health expands the concept of eHealth to include digital consumers, with a wider range of smart devices, connected equipment, and digital therapeutics. It also encompasses other uses of data and digital technologies for health such as the Internet of things, artificial intelligence, big data and robotics, and predictive and prescriptive analytics. Analytics can be for health system improvement, public health preparedness, or research and innovation."

Drawing on these definitions, but focusing more on the outcomes and stakeholders that contribute to digital health, our current working definition is:

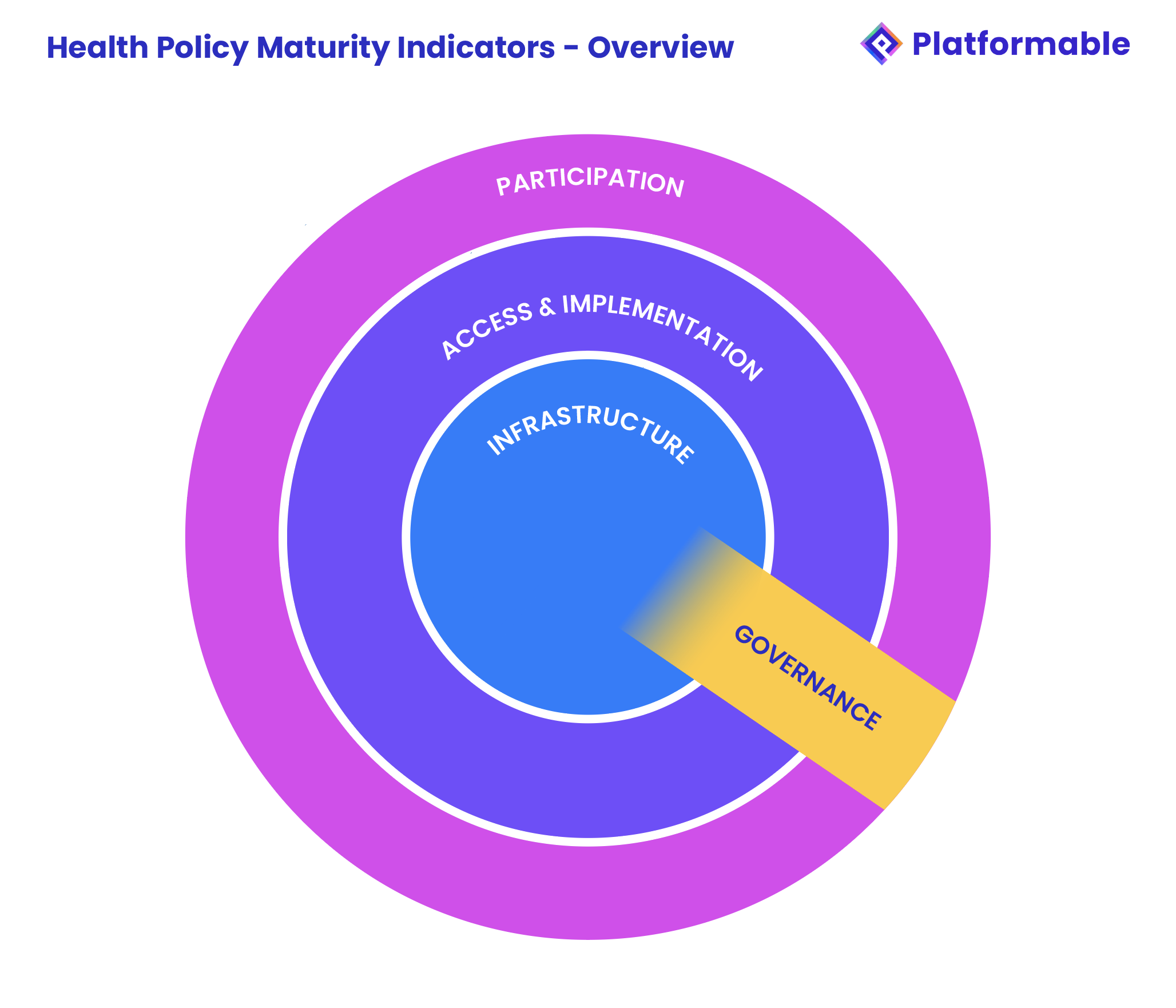

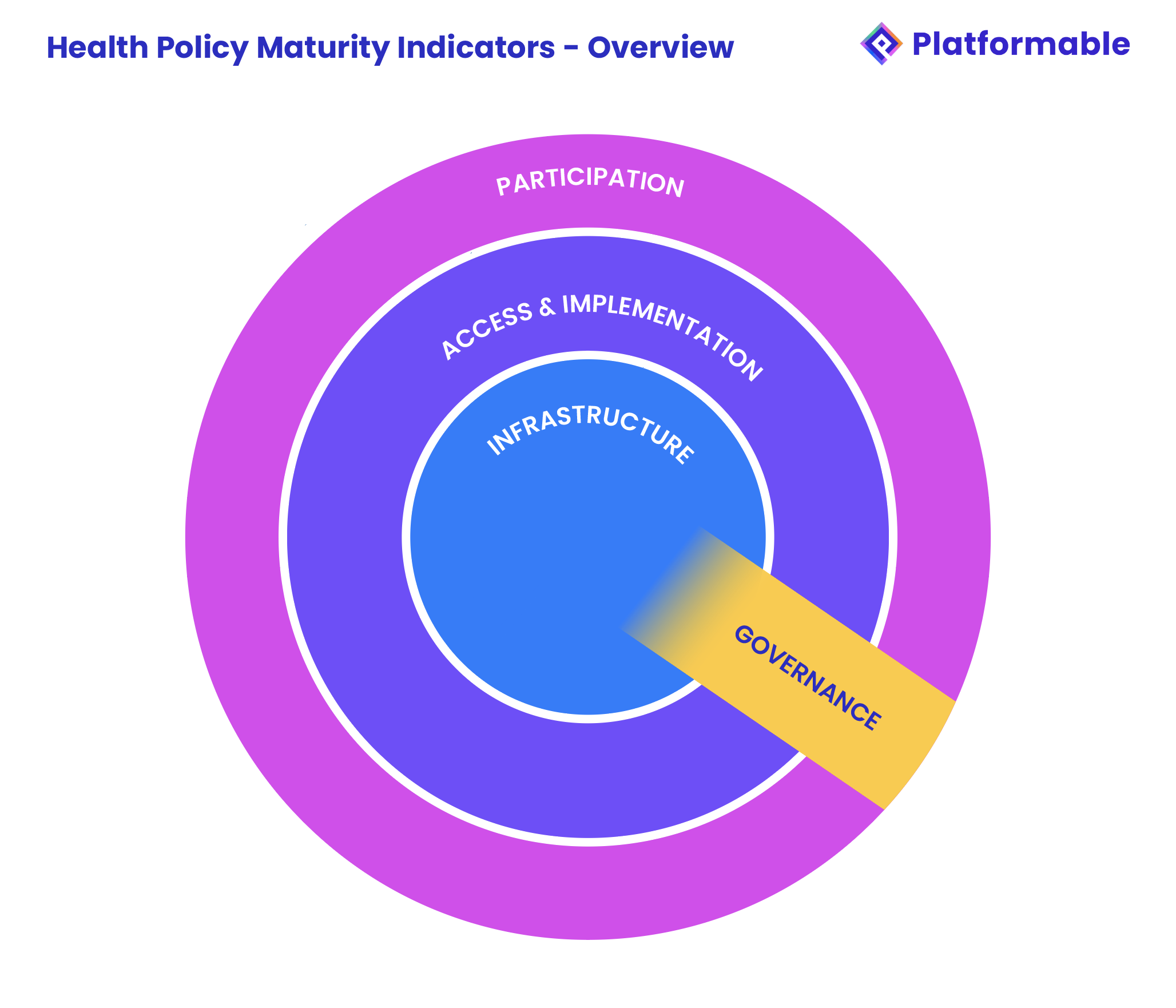

Our model looks out from primary use of health data to secondary uses and the ability for all stakeholders to participate in the ecosystem. Like in much of our work when we measure factors related to a digital ecosystem, we tend to categorise data points into three buckets:

- Infrastructure: The data infrastructure, legal frameworks, institutions and policies that foster digital ecosystems

- Access and implementation: The strategies and guidelines, processes, and enablement factors that enable digital ecosystems to achieve their goals and generate benefits/value

- Participation: The approaches that enable data to be shared and for stakeholders and new market players to enter and compete and collaborate responsibly, ethically and equitably.

This isn't an exact science. For example, we tend to find governance is a cross-cutting issue so we have governance metrics related to each infrastructure, access/implementation and participation but sometimes we categorise governance separately depending on the project, ecosystem lens, or client needs. But in general we see it as three concentric circles: in the centre are the foundational elements (infrastructure) that allow the digital ecosystem to operate. For example, in digital health this would be digitialisation and the availability of electronic health records. The next level out is the use of that data and digital capabilities to improve health outcomes (access & implementation), mostly for primary health objectives, but could also be starting to be used for improved health planning or further research. The third level out is the involvement of external stakeholders and the community (participation) in helping manage and participate using data and digital capabilities.

Assessing digital health maturity

We have identified some stakeholder groups that would benefit from being able to assess and compare the digital health policy context:

| Persona | Persona image | User statement |

|---|---|---|

| API tool providers and consultants |  | I need to understand how to measure the context in each market to be able to see how we should focus on the country for selling our products or services in that country. |

| Regulators |  | I need to understand the digital health regulatory environment in other countries in order to compare ours. I need to have a framework to assess digital health regulatory contexts. |

| Digital Health Policy Lead |  | I need a framework to measure our jurisdiction’s digital health context against an international benchmark and to identify where to focus our work next. |

| Health Tech |  | I need a framework to measure which countries are best suited to our products and services. |

| Non-Government Organisations |  | I need a framework to measure where we should focus our efforts and to compare our jurisdiction against others. |

| Equity Tech |  | I need a framework to measure the equity impacts of digital health policies |

| Data Governance Lead |  | I need a framework to measure our jurisdiction’s health data governance maturity, to identify where to focus our efforts, and to learn from global best practices. |

| Pharma Companies |  | We need a framework to assess jurisdictions we work in and to measure where we should best place our efforts. |

Existing frameworks to measure digital health maturity and ecosystem development

There are a few existing frameworks that offer some methodologies for us to build on, but we were challenged in finding a framework readily available that we could apply. Ideally, we believe in adopting a standardised model to help enhance comparisons and encourage interoperability and shared definitions and communication8. However, while there are benefits for each, there are several shortcomings with the existing models we have seen that made it difficult to adopt them:

OECD Policy Repository

This is an excellent tool that we drew on significantly when building out our indicators. However, the main goal of this tool is to identify where a country has some policies in place in the key areas that reflect digital health ecosystem characteristics. It is also crowdsourced, so countries can complete the data themselves and perhaps obfuscate some areas. For example, there is a categorisation for digital identity so users could add their country's digital identity policy, whether it mentions health specific application or not.

Digital readiness indicators are also discussed in detail in the OECD's Health at a Glance 2023 Report9. However, the scoring methodology is not described in detail so they could not be used in our approach. We also found some inconsistencies in the scoring that OECD made for some countries compared with our analysis.

But in any case, we'd love to weave this tool into our future digital products. For example, in a future iteration of our health policy dashboard, it would be good to have a page that lists the policy repository for each country.

WHO Global Health Monitor

The indicators used in the WHO Global Digital Health Monitor11 match our approach, with the exception that we do not look at cross-border data interoperability. These WHO digital health indicators also do not look at patient digital literacy or participation in decision-making, and do not include metrics to discuss wider ecosystem participation and mechanisms to involve a range of stakeholders in digital health collaborations.

The scoring methodology appears to draw from the WHO-ITU Digital Health Assessment Toolkit10, however, we are unclear whether top scores for each country are shown or averages. For example, in one area Canada receives the highest score of Phase 5 but when looking at each group of indicators, they may score top marks for one of five or six indicators 3 areas of grouping, and lowest for four indicator groupings yet are scored highest overall. The methodology suggests that the average score for the country is used, but it appears this is the average for only those indicators where there is a score, and not for the indicators where no values are recorded. But the methodology is not clear and several proxy datasets are used. The data is also often out of date (2023 is the latest data used, but is often blank).

ODI/Roche Assessment of secondary use of health data policies

For the Open Data Institute (ODI) and Roche, I was lead author in work with Dr Milly Zimeta, Dr Jeni Tennison and Mahad Alassow where we developed a set of indicators to measure the readiness of European and neighbouring countries to make use of health data for secondary uses (for example in service planning, personalised health care, resource optimisation, investment allocations, new research, and so on). That model was based on the ODI's 6 core manifesto points at the time and was later updated to match their new policy principles in a followup study for Western Balkan nations. We drew on that research and experience for Platformable's indicators as well, but extended to primary use of data as well for this work as we are looking at digital health in its entirety, not just secondary use opportunities.

Other models assessing global health policy maturity

There are other studies and approaches that we drew on:

- Laura Maaß's excellent thesis is thorough and comprehensive12 and details 272 indicators in total across 4 domains: legal, ICT, application and social. Detailed scoring methodology is also provided. We chose not to implement this digital public health maturity index as it was too resource intensive for our client studies. We see this index as being more suited to internal government policy leads who want to score their own systems and identify a maturity roadmap. However, we did assess how our metrics align with the indicators and checked the remaining indicators to see if there were key areas we were overlooking.

- The work by Leanna Woods et al for the Australian Digital Health Agency13 proposes an approach to assessing digital health maturity models. This work includes a summary of the characteristics that would be included in a maturity assessment framework, which are aligned with our indicators. This work is also useful for describing how policy leads and others could use our analysis to then build their own strategy, a discussion we will return to at the end of this series.

- The study on national eHealth strategy frameworks across Africa by Isaac Iyinoluwa Olufadewa et al14 was also useful. They created a National Strategy Rating Tool, drawing on frameworks including the WHO-ITU Toolkit methodology mentioned above. Their scoring is focused on a higher level of assessment and scoring, focusing on whether strategies exist, level of funding and implementation activity and recency of progress. This fascinating and first-of-its-kind study aims to demonstrate the overall prioritisation and maturity of digital health strategy setting across Africa and sets the groundwork for then digging deeper to explore what should be in a country-level digital health strategy.

One piece of work that we want to highlight as particularly unhelpful and disappointing is a white paper on the "Digital Health Network Economy"15 released in January 2025 by the World Economic Forum in partnership with Capgemini. We are particularly disheartened by Capgemini's involvement in this work, given their data governance leadership in other areas. While the report does suggest eight enablers of innovation that align with many of the indicators we chose for our digital health assessment maturity, the WEF goes on to describe an ecosystem that consists solely of the public and private sector. There is no discussion on how newer market players can enter fairly and compete and collaborate with incumbents, no discussion of the participation of standards bodies (yet interoperability is mentioned throughout as essential) or academic research institutions, or patient organisations, or media, or community advocates. Regulator descriptions focus on ensuring data privacy without recognising the emerging health data access type institutions. It is filled with lines like "By gathering insights from public and private stakeholders, business models can be established that align financial gain with patient benefits, creating incentives that foster a collaborative approach to health data sharing." What does that even mean?

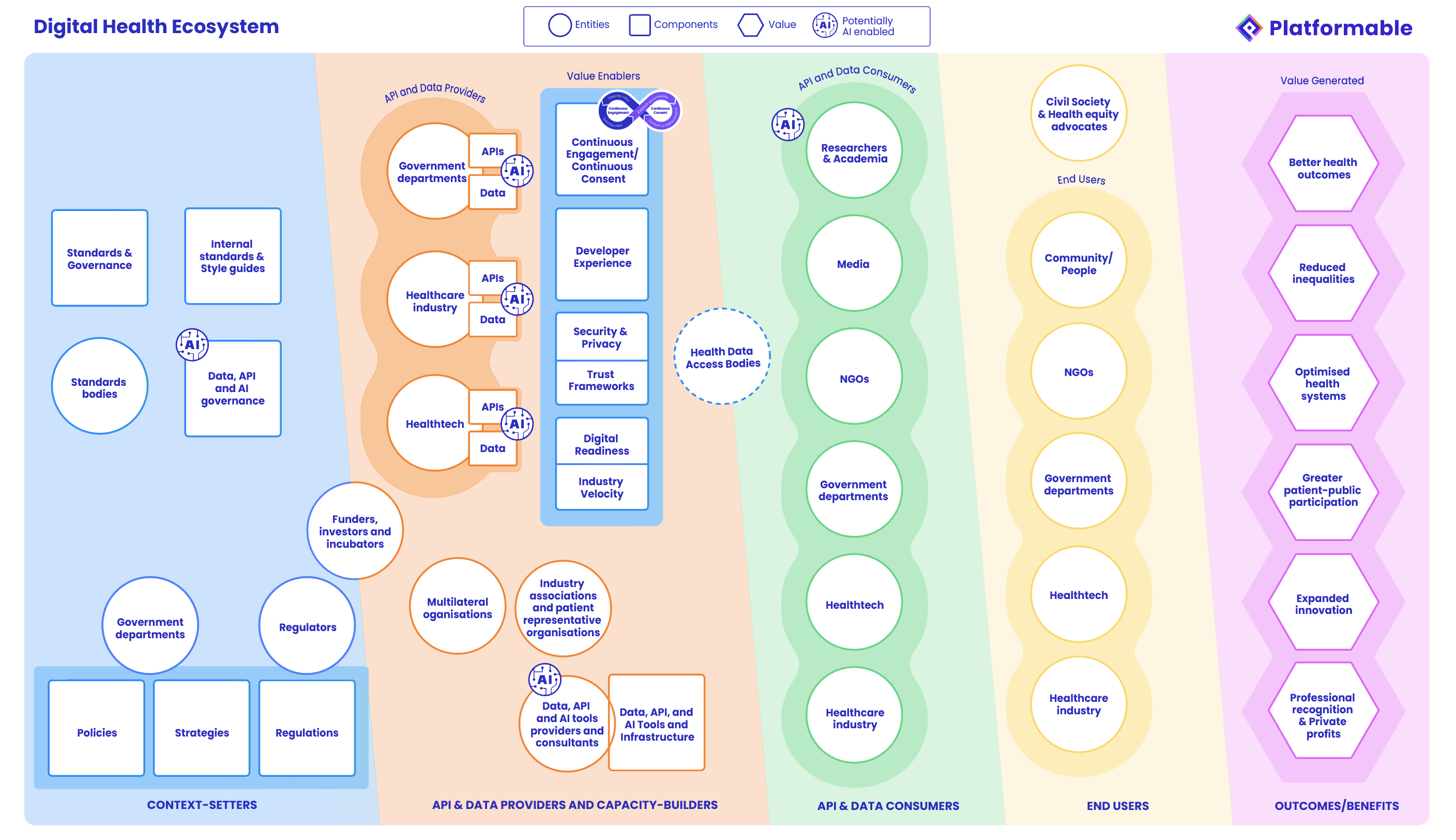

Digital health ecosystem and theory of change

We have mapped the digital health ecosystem which can also be used to describe a theory of change for the benefits expected to be generated from responsible, equitable, ethical and increased use of health data. Using this theory of change and ecosystem model allows us to identify what characteristics we should measure to determine whether the health data ecosystem would generate expected value, that is, how mature each component is in order to assess the overall maturity of the local digital health ecosystem.

Drawing on this theory of change, and the benefits and shortcomings of existing frameworks, we mapped our health data ecosystem assessment framework and identified a range of indicators. For a current client project, the focus was on indicators that could be measured across Canada and provinces and digestible in discussions on the progress of data sharing and interoperability in particular. For that project, we chose 15 core indicators, however our full set extends to 25 potential indicators which we think is comprehensive and achievable to analyse to get a full picture of the health strategy characteristics of a particular area without getting too in the weeds with data.

In our next article in this series, we will dig further into the indicators, focusing on how our indicators align with other models. We will then describe each indicator and the benefits and limitations of each and how we are scoring them. We will then conclude the series with a look at how to use these indicators yourself and how they can be further developed.

If you would like to discuss this work with us further, please email me at mark@platformable.com or complete the calendly below. (While our website does not use cookies as part of our data privacy principles, the calendly embed does, so you have to click and accept or reject their cookies first for making a booking.)

Article references

Lee J, Park YT, Park YR, Lee JH. Review of National-Level Personal Health Records in Advanced Countries. Healthc Inform Res. 2021 Apr;27(2):102-109. doi: 10.4258/hir.2021.27.2.102. Epub 2021 Apr 30. PMID: 34015875; PMCID: PMC8137875. Cited at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8137875/

We stress that this is our distinction that we use and, of course, would like to see be adopted more generally, but in our current work in Canada for example, we are seeing that governments are using the term digital health to describe modernisation strategies, what we would call ehealth strategies. So there is still some confusion and mixed terminology, but we do note that recently, the WHO definition of digital health (ass discussed in the following section) also highlighted the evolution of 'digital health' over 'ehealth'.

From their website: https://www.who.int/europe/health-topics/digital-health

From the Australian Digital Health Agency's Digital Health Strategy. Cited at: https://www.digitalhealth.gov.au/national-digital-health-strategy/about-the-strategy

Fatehi F, Samadbeik M, Kazemi A. What is Digital Health? Review of Definitions. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2020 Nov 23;275:67-71. doi: 10.3233/SHTI200696. PMID: 33227742. Cited at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33227742/

From the OECD Digital health chapter in Health at a Glance 2023: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/health-at-a-glance-2023_7a7afb35-en/full-report/component-6.html

Obligatory to mention this: https://xkcd.com/927/

Discussed here but scoring details to be able to replicate their model is not given: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/health-at-a-glance-2023_7a7afb35-en/full-report/component-6.html

There are currently two sites for this: https://data.who.int/dashboards/gdhm/overview and https://digitalhealthmonitor.org/

Woods L, Eden R, Duncan R, Kodiyattu Z, Macklin S and Sullivan C (2022) Which one? A suggested

approach for evaluating digital health maturity models. Front. Digit. Health 4:1045685. Cited at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/365718015_Which_one_A_suggested_approach_for

_evaluating_digital_health_maturity_models

Isaac Iyinoluwa Olufadewa, Opeyemi Paul Iyiola, Joshua Nnatus, Kehinde Fatola, Ruth Oladele, Toluwase Olufadewa, Miracle Adesina, Joseph Udofia, National eHealth strategy frameworks in Africa: a comprehensive assessment using the WHO-ITU eHealth strategy toolkit and FAIR guidelines, Oxford Open Digital Health, Volume 2, 2024, oqae047, https://doi.org/10.1093/oodh/oqae047. Cited at: https://academic.oup.com/oodh/article/doi/10.1093/oodh/oqae047/7905772?login=false

Shown here but we don't recommend as a source. It discusses data collaboration without any patient, academic, or public sector involvement and frames health as a business model opportunity throughout: https://www.weforum.org/publications/better-together-building-a-global-health-network-economy-through-data-collaboration/

Mark Boyd

DIRECTORmark@platformable.com